Source: www.rdhmag.com

Authors: Ben F. Warner, DDS, MD, MS, Cleverick “C.D.” Johnson, DDS, MS, Gary N. Frey, DDS, Michele White, DDS

This review of oral white lesions and their identifying factors can be a guide for dental hygienists to determine whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

A complete, periodic oral exam plays a vital role in evaluating the overall health of dental patients. New and established patients’ well-being can be supported by their relationship with the dental team. Any new or existing leukoplakia-type findings can be biopsied, identified, monitored, or referred for appropriate care. These lesions are characterized as white patches or plaques that “cannot be wiped off and cannot otherwise be described clinically as any other disease.”1

Discerning whether an oral white lesion is of concern is dental health-care professionals’ duty. While the majority of oral leukoplakia presents without symptoms and few patients complain of discomfort, a thorough medical history and oral exam are necessary to assure oral health. Dental hygienists are strategically positioned to support optimum patient health by observing relevant clinical findings.

We conducted a literature review of commonly found oral white lesions for this article. Dental professionals can observe the clinical features of these lesions and distinguish those that need referral to a health-care specialist. The following are examples of commonly found white lesions observed in the oral cavity.

Frictional keratosis

Frictional keratosis (figure 1) is a white keratotic lesion on the oral mucosa that results from a chronic mechanical friction by various oral irritants or habits. These lesions appear on the keratinized or nonkeratinized tissues and present as diffuse plaques, pale translucent to dense white and irregular.2 As the name implies, frictional keratosis is diminished with removal of the causative factor. If cessation of the irritant does not result in clinical improvement, a biopsy should be performed.

Smokeless tobacco keratosis

Smokeless tobacco can produce a thickened layer of keratin at the site of tobacco placement (figure 2). Variations in clinical appearance are due to the frequency and the amount of tobacco used.3 Common sites for smokeless tobacco keratosis are the maxillary and mandibular vestibules. Recommendations by the dental hygienist and dentist are for cessation of use, or at least altering the site of tobacco placement if the patient is unable to stop. These measures can aid in the reduction of this lesion.2

Leukoedema

Leukoedema (figure 3) presents as a diffuse, milk-white, opalescent lesion on the bilateral buccal mucosa that disappears when the mucosa is stretched. It is most common in the African American population, with reports of patients having this feature since early childhood. Consequently, it is considered a variation of normal.4 Dental hygienists can distinguish this lesion more easily with findings from the clinical exam and information from the patient’s dental history.

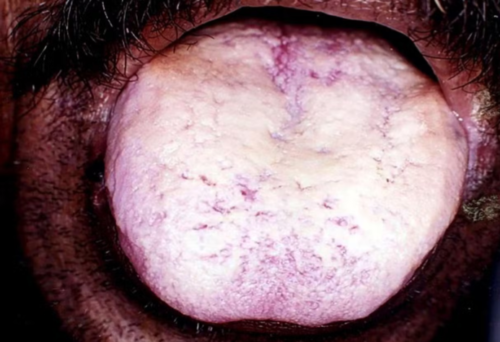

Oral candidiasis

Oral candidiasis (figure 4) is a fungal infection caused by Candida albicans that occurs secondarily to immune suppression. The most common oral form, acute pseudomembranous candidiasis, presents as a white, red, or mixed-color lesion. Findings occur in ages ranging from infants through seniors and immunocompromised populations. Most often, oral candidiasis is displayed as a white patch that can be “easily removed with gauze.”5 This is a key sign that helps distinguish this lesion from others. Candidiasis lesions are often asymptomatic and can be found on the tongue, labial and buccal mucosa, gingiva, hard and soft palates, and the oropharynx. Sometimes symptoms include a burning sensation, bleeding, and changes in taste perception. Initial treatment includes oral antifungal pastilles such as nystatin.5

White sponge nevus

White sponge nevus (figure 5) is a rare genetic skin disorder that presents as a diffuse, symmetrical, thickened, corrugated white lesion on the buccal mucosa.4 Though significant in appearance, this benign lesion requires no treatment.

Aspirin burn

Pain is one of the main symptoms patients present with to dental offices. Aspirin burn (figure 6), or acetylsalicylic acid burn trauma of the gingiva and oral mucosa, present secondarily to patient self-medication with over-the-counter pain relief medicines. Analgesics can cause chemical burns when taken incorrectly and placed directly on the gingiva. These wounds present as irregularly shaped white lesions and can have ulcerative-type lesions at the base. Treatment includes discontinuing use of the causative agent and palliative measures.6

Lichen planus

Lichen planus (figure 7) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that can involve the skin, hair, nails, and mucosal surfaces. The most common oral sites are the buccal mucosa, tongue, and gingiva. These lesions present as reticular or lacy lines, known as Wickham striae. Usually asymptomatic, some patients report occasional burning sensation or taste alterations.7 The cause of lichen planus has been associated with hepatitis C, influenza vaccine, certain medications, and as an autoimmune reaction in people with genetic predisposition.8 In addition, women are twice as likely to present with symptoms. Treatment includes steroids, antihistamines for symptomatic itching, and eczema medications; no treatment is also an option. Symptoms can resolve on their own in approximately two years.9

Oral hairy leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia (figure 8) presents most often as a white corrugated lesion on the lateral border of the tongue. The Epstein-Barr virus is known to be the causative factor of this false leukoplakia, and signifies the transition of HIV infection to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).10

Squamous cell carcinoma

In the US, oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OC-SCC; figure 9) is the most common malignancy of the head and neck, apart from nonmelanoma skin cancer. Risk factors include all forms of tobacco use, alcohol abuse, and the human papillomavirus (HPV).11 OC-SCC is preceded by leukoplakia (white), erythroplakia (red), or erythroleukoplakia mixed/speckled-type lesions that present on the tongue, floor of the mouth, buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, retromolar trigone, and soft palate.11 The value of the clinical oral exam cannot be underestimated. Due to the frequency of the hygiene schedule, dental hygienists are a first line of defense in knowing their patients’ oral health and, as such, can play a vital role in early intervention and saving lives.

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL; figure 10) is described as an advancing form of leukoplakia that starts as a flat, hyperkeratotic white patch and progresses to a verrucous or papillary form and then finally to invasive squamous cell carcinoma.12 PVL has a gender predilection, with a female to male ratio of approximately 4:1, a mean age of 66 years, and a site preference for the buccal mucosa, palate, tongue, and gingivae.12 Conventional risk factors are unknown; however, PVL is known for its aggressive ability for recurrence at 90%, even after excision.12

Benign migratory glossitis

Benign migratory glossitis (BMG; figure 11), or geographic tongue as it is commonly referred, is characterized by a loss of filiform papillae13 or epithelium on the dorsum and lateral borders of the tongue. The lesions present with demarcated, irregular, erythematous (red) areas with a slightly raised white border. BMG is often asymptomatic, has a predilection for females and children, and frequently diminishes with age. Due to healing of these lesions at the border and proliferation of the inflammatory process, this presentation appears to migrate.14 The disease is characterized by periods of remission, requires no treatment, and has been associated with psoriasis and other conditions.14

Oral cicatricial pemphigoid

Pemphigoid (figure 12) is a rare autoimmune disease that can affect the oral cavity. It causes ulcerative lesions that can be extremely painful. The cause of pemphigoid is unknown; however, an abnormal response by the body’s immune system resulting in an attack on the oral tissues seems likely. Treatment options to suppress the body’s immune system include topical and systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive medications.15

Advocating for our patients’ well-being

The diagnosis of carcinoma depends upon histopathologic analysis of biopsied specimens.16 Knowledge of the spectrum of normal oral mucosa anatomy is the foundation for clinical recognition of leukoplakia and other lesions. Dental hygienists are in a key position to effectively screen for oral cancer and potentially malignant lesions. Patients often present every three to six months for their dental hygiene oral care, allowing for identification and early intervention of white lesions that are of concern. Advocating for dental patients’ oral health can lead to well-being in overall health—a common goal shared by health-care professionals throughout the world.

Editor’s note: This article appeared in the October 2023 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

1.Definition of leukoplakia. World Health Organization. 2017.

2.van der Wal JE. Frictional keratosis. In: Slootweg P, ed. Dental and Oral Pathology. Encyclopedia of Pathology. Springer; 2016. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28085-1

3.Müller S. Frictional keratosis, contact keratosis and smokeless tobacco keratosis: features of reactive white lesions of the oral mucosa. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(1):16-24. doi:10.1007/s12105-018-0986-3

4.Huang BW, Lin CW, Lee YP, Chiang CP. Differential diagnosis between leukoedema and white spongy nevus. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(4):554-555. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2020.05.018

5.Taylor M, Brizuela M, Raja A. Oral candidiasis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

6.Ogbureke EI, Johnson MWC. Oral aspirin burn. J Greater Houston Dent Society. Fall 2021.

7.Olson MA, Rogers RS, Bruce AJ. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(4):495-504. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.023

8.Das S. Lichen planus. Merck Manuals. Updated September 2022. www.merckmanuals.com

9.Lichen planus. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/lichen-planus

10.Rathee M, Jain P. Hairy leukoplakia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

11.Chi AC, Day TA, Neville BW. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma – an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(5):401-421. doi:10.3322/caac.21293

12.Speight PM, Hunter KD. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. In: Slootweg PJ, ed. Dental and Oral Pathology. Encyclopedia of Pathology. Springer; 2016.

13.van der Wal JE. Geographic tongue. In: Slootweg PJ, eds. Dental and Oral Pathology. Encyclopedia of Pathology. Springer; 2016:181-183. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28085-1_711

14.Gonzaga HFS, Chaves MD, Gonzaga LHS, et al. Environmental factors in benign migratory glossitis and psoriasis: retrospective study of the association of emotional stress and alcohol and tobacco consumption with benign migratory glossitis and cutaneous psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(3):533-536. doi:10.1111/jdv.12616

15.Tolaymat L, Hall MR. Cicatricial pemphigoid. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

16.Sciubba JJ. Oral leukoplakia. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6(2):147-160. doi:10.1177/10454411950060020401

17.Lauritano D, Boccalari E, Di Stasio D, et al. Prevalence of oral lesions and correlation with intestinal symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2019;9(3):77. doi:10.3390/diagnostics9030077

18.Patil S, Rao RS, Majumdar B, Anil S. Clinical appearance of oral candida infection and therapeutic strategies. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1391. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01391

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.