Source: biotechin.asia

Author: Manish Muhuri

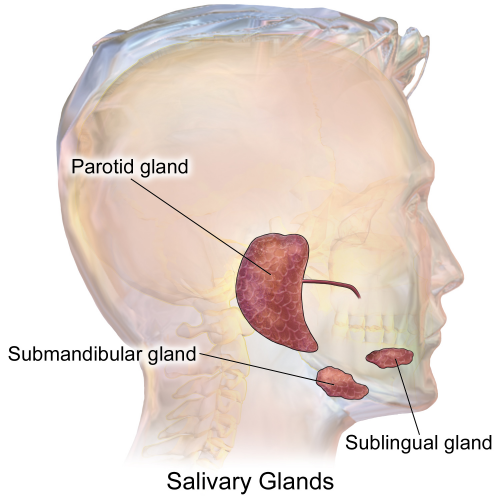

Saliva is a watery substance secreted by the salivary glands located in the mouth. Saliva is essential for good health, as it assists in speaking, swallowing, food digestion, preventing oral infections in addition to many other tasks. Without normal salivary function the frequency of dental caries, gum disease (gingivitis), and other oral problems increases significantly.

Dysfunction or reduction in activity of salivary glands can be caused by many factors, including diabetes, radiation therapy for head and neck tumors, aging, medication side effects, and Sjögren’s syndrome.

Sjogren’s is an autoimmune disease where the body attacks its own tear ducts and salivary glands. Patients suffering from this disease have severely dry mouth. No treatments are currently available for dry mouth. Salivary glands, unfortunately, have very little regenerative capacity.

The title must have left you wondering about the correlation between silk and saliva – what do they have in common? They are both actually part of a unique experiment going on in San Antonio, a study that could change the lives of millions of people who suffer from dry mouth.

Chih-Ko Yeh , BDS, Ph.D., and Xiao-Dong Chen, MD, MS, Ph.D., of the UT Health San Antonio School of Dentistry decided there had to be a better way to help people than try to develop drugs and figured that stem cells may help solve a common, painful problem.

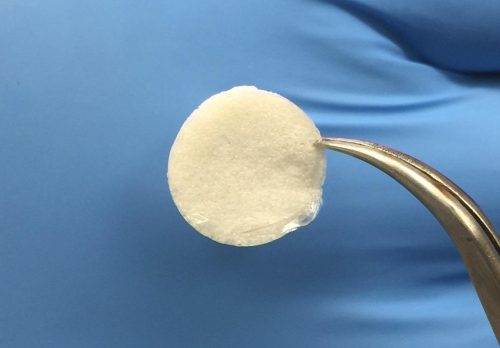

Yeh said the idea is to use stem cells from the patient’s own body derived from bone marrow to grow new salivary gland cells. In order to coax those stem cells into becoming the right kind of cell, researchers are using silk from worms and spiders as scaffolding.

Silk is a natural protein that mimics the micro-environment of the salivary gland. Silk works well, the scientists say, because it’s biodegradable, flexible and porous, providing easy access to the oxygen and nutrition the cells need to grow. Chen and his partner are using rats to test out ways to place the cells in the body to jump-start tissue repair.

“Then we can deliver those cells to a damaged salivary gland by injection, local injection,” Chen explained.

Yeh and Chen’s early work was published in the journal Tissue Engineering.

Experts said this leap into regenerative medicine is intriguing while patients like Willette are holding out hope. “There’s no reason why they shouldn’t be able to find something to help with this,” Willette said.

In 2016, the researchers received a grant of more than a million dollars from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (part of the National Institutes of Health) to continue their promising work.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.