Source: web.musc.edu

Author: Leslie Cantu

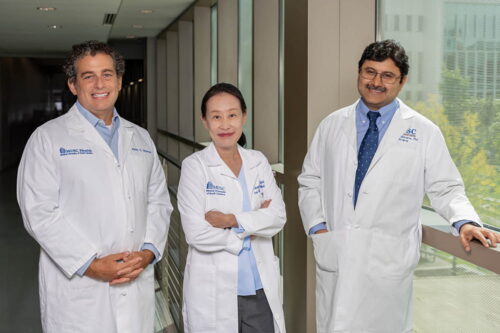

Jason Newman, M.D., Angela Yoon, D.D.S., and Shikhar Mehrotra, Ph.D., are working together on a project to develop a personalized vaccine to prevent oral cancer from returning. Photo by Clif Rhodes

Interdisciplinary innovation is a hallmark of MUSC Hollings Cancer Center, and it doesn’t get much more interdisciplinary than this – three people, one each with an M.D., a D.D.S., and a Ph.D., working together to develop a new type of personalized vaccine to prevent oral cancer recurrence.

“The amazing thing to me is that Jason Newman and I started on the same day at MUSC, which was March 1 of last year. He came from UPenn. I came from Columbia, and Shikhar has been at MUSC forever. It’s just three different people who never knew each other before that time, and then we somehow got together and the synergy was there,” said Angela Yoon, D.D.S.

Yoon, a professor in the James B. Edwards College of Dental Medicine who focuses on cancer biomarkers and immunomodulatory therapy, is leading the effort in collaboration with the two professors from the College of Medicine: Jason Newman, M.D., Head and Neck Cancer Division director, and Shikhar Mehrotra, Ph.D., scientific director of the Center for Cellular Therapy.

They’re getting their project started using funding provided by Hollings. Periodically, Hollings awards funds to MUSC departments as a way to reinvest in faculty members who are conducting cancer research. Participating in clinical trials and on scientific committees and writing new clinical trials all take up a lot of time – time that often comes with few to no resources to support the work. Hollings developed this reinvestment program to ensure that departments had the resources to promote the clinical research mission. It’s yet another remarkable aspect of Hollings’ commitment to new research, Yoon noted.

Her project involves isolating the immune cells that have responded to the immunotherapy used against a squamous cell oral cancer, strengthening and expanding the immune cells, and then injecting them back into the same person so they’re ready to respond at the first sign that the cancer is returning – an unfortunately common aspect of oral cancer.

“Currently, people are using the term ‘cancer vaccine’ interchangeably with ‘immunotherapy,’ which they’re using to kill the tumor cells – not as a preventive measure,” Yoon said. “So this is going to be one of the first studies to actually give it almost like a COVID vaccine.”

It’s an outgrowth of her clinical trial that’s shown great promise using imiquimod, a cream approved for skin cancer, on oral cancers ahead of surgery. Imiquimod both destroys tumor cells and also prompts T-cells in the immune system to attack the cancer. The topical medicine has been effective in shrinking tumors, which means that surgeons don’t have to remove as much tissue from the patient’s mouth.

For this project, Newman will remove tumors from a patient’s mouth. The tissue is then brought to a waiting pathologist, who ensures that the surgeon has gotten everything. From there, Yoon will take a small sample of the tumor to Mehrotra. Mehrotra’s job, then, is to find the immune cells that have shown a response to the cancer – not every immune cell responds to every invader – and coax them into multiplying into an army of memory T-cells tuned to the specific profile of that person’s cancer.

If it works, Yoon expects that patients would need a yearly injection of the personalized vaccine – but first group members must conduct the preclinical research. Their goal is to apply for investigational new drug approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and then to apply for a larger grant to enable clinical trials.

It’s a long process, which Yoon said wouldn’t be possible without Newman and Mehrotra.

“I feel really lucky,” she said.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.