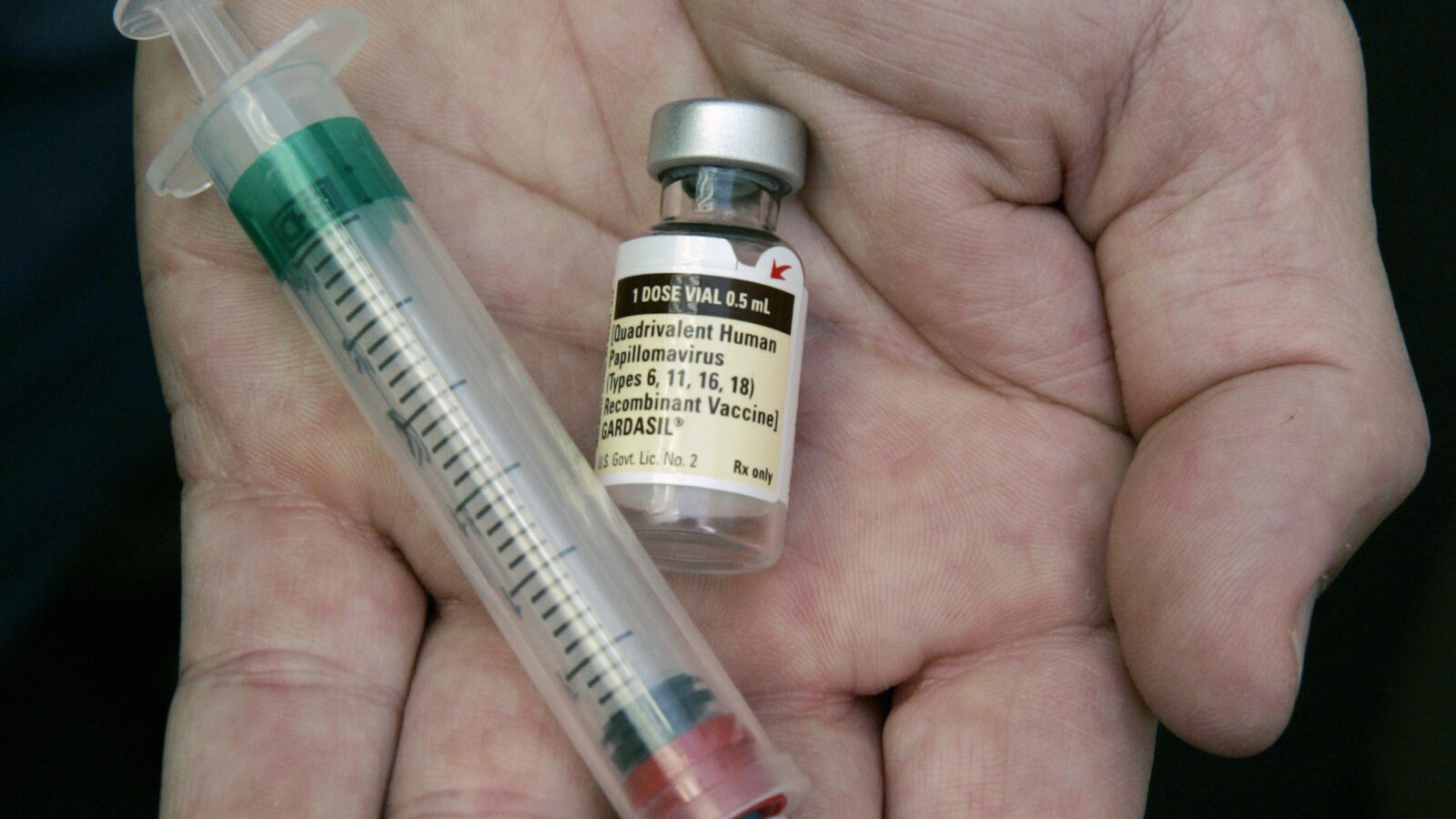

For the past decade, evidence has suggested that Gardasil, the HPV vaccine, could stem an epidemic of throat cancer. But it has also never received approval from the Food and Drug Administration for that use — and it was unclear if it ever would.

On Friday, the agency granted that approval, clearing the latest version of the vaccine, Gardasil 9, to prevent a cancer that affects 13,500 Americans annually. The decision was announced by Gardasil’s maker, Merck.

The decision doesn’t change recommendations about who should get the vaccine, which is already recommended for females and males ages 9 through 45 to prevent cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer as well as genital warts. But cancers of the head and neck — mainly those of the tonsils and throat — have been left off the list.

It’s a striking omission, because head and neck cancer, mostly cancer of the throat, is the most common malignancy caused by HPV, the human papilloma virus, in the U.S. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there are 35,000 cases of HPV-related cancer in the U.S. annually. On top of the 13,500 cases in the throat, 10,900 are cases of cervical cancer.

“That’s excellent news,” said Stewart Lyman, a pharmaceutical consultant whose doctors discovered a tumor in his throat in 2016. It was removed surgically, and was caused by HPV. “To have this extended to head and neck cancer is really very helpful for helping to inform the public that this serious disease, which has significant morbidity and mortality associated with it, can be prevented with the vaccine,” Lyman said.

Marshall Posner, the director of head and neck medical oncology at the Tisch Cancer Institute, said the approval is “a good thing for the FDA to do” and that he would be “thrilled” if head and neck cancer cases could be reduced through vaccination in coming decades. He said he has “every expectation” that an HPV vaccine would reduce cancer rates.

The original version of the Gardasil vaccine was approved in 2006 for girls and women between the ages of 9 and 26 based on data from clinical trials showing that the vaccine, by preventing HPV infection, could also prevent precancerous cervical lesions. But such lesions don’t exist in head and neck cancer, and it was not clear how to prove the vaccine’s efficacy.

Maura Gillison, now a professor at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, first connected a subset of head-and-neck cancers to HPV in 1999. But then she and other epidemiologists noticed something: The number of head and neck cancers was rising rapidly, and HPV seemed to be a culprit. What’s more, these sexually transmitted cases seemed different — and somewhat easier to treat. The most common victims were middle-aged men who had contracted the virus decades before.

The FDA is granting what’s known as an accelerated approval, meaning that the decision is contingent on the production of more data and is based on what’s known as a “surrogate endpoint” — an indication that a medicine works that is not foolproof. In this case, the FDA is approving the drug based on data on preventing anogenital infection. In February, Merck began a study of 6,000 men that will test whether patients who receive the vaccine are less likely to get persistent HPV infections in their throats.

Adding another disease to the approval does impact what Merck can say to doctors and patients about HPV and head and neck cancer. “It’s something that was missing in the label,” said Alain Luxembourg, director, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories. “It is something missing in the conversation between patients and doctors.”

Otis Brawley, an oncology and epidemiology professor at Johns Hopkins University, said that while he is usually opposed to surrogate endpoints, in this case he is comfortable with the decision. “There’s already enough reasons to vaccinate for HPV in men,” he said, adding that doing so broadly might make it possible to eradicate the virus, and the cancers it causes.

For Gillison, who spotted the emergence of HPV throat cancer, it came too late. She pushed Merck to do a study, and said that the one that started in February is coming “10 years plus after when it would have really mattered.” She also thinks that the real reason for the decision is the weight of epidemiologic evidence that she and others produced.

“The fact of the matter is that this approval probably has little whatsoever to do with the anal data per se,” Gillison wrote via text message. “It is because the FDA is made more comfortable with inference because of all the data that has been generated regarding the relationship between oral HPV infection and HPV vaccination outside of vaccine trials in the last 10 years.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.