Source: www.cbc.ca

Author: Glenn Deir

This is a First Person column by author Glenn Deir, who lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Glenn Deir has special thanks for the robot who operated on his tonsil cancer.

Long before I had cancer, and long before I lived in Japan, the rock band Styx released a synthesizer-drenched song with the hook “Domo arigato, Mr. Roboto.”

Forty years later I, too, found myself thanking a robot. Its name is da Vinci.

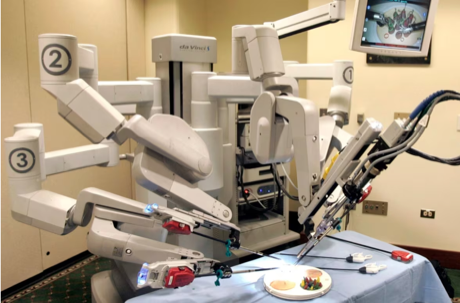

Da Vinci resembles a giant spider with four arms, and my journey to lying beneath those arms began with a niggling problem: I was having discomfort swallowing. Even sipping water sometimes stung.

A flexible scope up my nose and down my throat revealed an apparent ulcer on my tonsil, the right tonsil, my one remaining tonsil. But given my history, my doctor couldn’t ignore it.

Ah, my history.

Sixteen years ago, I contracted cancer in the left tonsil thanks to the human papillomavirus. That’s the same virus that causes cervical cancer. Most folks shed the HPV virus with no harm done, but I had crappy luck. The subsequent radiation had me retching into a toilet for weeks. I turned into an advocate for the HPV vaccine.

“Sex gave me cancer,” I used to say. “You don’t want your little boy to grow up and go through what I went through.”

What I wanted to ask Dr. Boyd Lee was, “So, what’s involved with this biopsy?” A sensible, open-ended question which made no assumptions and should have laid the groundwork for serious discussion. Instead, what came out of my mouth was, “So, what’s involved with this autopsy?” We both burst out laughing. The “autopsy” meant taking a snip of the tonsil for the pathology lab.

In the meantime, we both had travel plans. I was off to Brooklyn for my 11th Bruce Springsteen concert. Dr. Lee was bound for France. Three weeks later, vacation stories took priority over the pathology report. He had sought writing inspiration in cafés. I had yelled “Bru-u-u-u-ce” from the nosebleeds in Barclays Center.

My wife and I weren’t done travelling. We were a week away from a European vacation. “Are you going to f@#% up my holiday?” I asked. He nodded yes, said he was sorry and told me I had a new cancer in familiar territory.

“You owe me a beer,” I told him.

“I owe you more than that,” he replied.

New cancer, old nemesis

The cancer diagnosis wasn’t the worst part. The worst part was knowing I was going to make my wife cry, again. Sixteen years ago, Deb’s eyes were often red and wet. I remembered her fear that I might die on the operating room table. Her helplessness as the doctors made me sicker and sicker before I could heal. All that despair came rushing back. What kind of husband makes his wife sob?

The apartment in southern Spain — gone. The walking holiday in England’s Yorkshire Dales — gone. All cancelled and traded for a 20-minute stroll to the cancer centre. The patient room might have had a coat of paint since I was last there. I told the medical team, “I love what you’ve done with the place.”

My new cancer was caused by my old nemesis — HPV. We discussed whether removing the right tonsil 16 years ago would have prevented the cancer today. Not necessarily. Cancer can set up in the tonsil area even after a tonsillectomy. What if I had taken the HPV vaccine after my first cancer? Too late. It was already in my DNA.

The next step was a PET scan. The cancer lit up the tonsil like a Christmas tree bulb.

The peanut-shape extended to the back of my tongue. Apparently, the back of the tongue is where we taste bitter flavours. Deb held out hope I might lose some of my bitterness. Not a chance.

Given removing the cancer involved delicate cutting of the tonsil, tongue and throat, Dr. Lee offered to refer me to a surgeon in Halifax who used a robot named da Vinci. There is no da Vinci in Newfoundland and Labrador. It’s an expensive piece of equipment. Halifax’s cost just over $8 million.

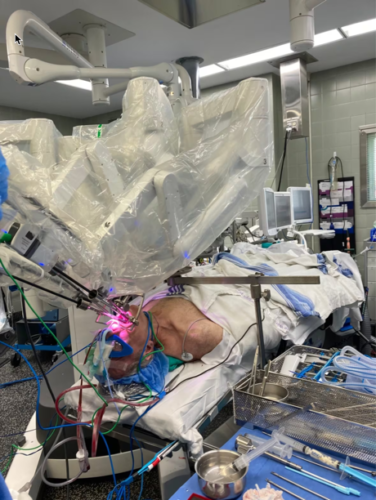

Da Vinci’s “fingers” can go where the human hand cannot. The surgery is less invasive, the complications fewer, the recovery quicker. But da Vinci is not R2-D2. It does not act autonomously. It does what its master directs, and in my case its master was Dr. Martin Corsten. He sits behind a console controlling da Vinci’s arms while peering through high-definition cameras.

The reporter in me couldn’t be held back. I asked Dr. Corsten if someone could take photos.

Not a problem. He’d probably get a medical student to do it. I wasn’t even the first patient to ask. Happens all the time. So much for my scoop. Deb snorted, “And you thought you were so special.”

July 13. 7.30 a.m. I’m first up on the table. A nurse shows me one of da Vinci’s arms. The robot is so popular Dr. Corsten only has access every second Thursday. It’s also used for urologic and gynecological procedures. “I hope somebody gave that thing a good scrubdown,” I said.

The operation took 2½ hours. It was more complicated than Dr. Corsten anticipated. The previous radiation had made the tonsil stiff; it didn’t pull away easily. The tumour on my tongue was the size of a large cherry. He also had to rotate a muscle to close a gap in my throat. I woke up with a feeding tube up my nose and an incision that ran the full length of my neck. I was a cross between the Elephant Man and Frankenstein.

The feeding tube is gone now, but I was over five weeks on a strictly liquid diet. I’m still retraining my throat to swallow and my tongue to speak. The latter challenge was particularly evident while I was watching an episode of Star Trek Discovery. Klingon warlords were pontificating about blood oaths and honour, all in the guttural sounds of Klingon, of course. Deb came into the room, listened for a few moments and declared, “They don’t speak any better than you.”

The da Vinci Surgical Robot is pictured at a hospital in Pittsburgh. (Keith Srakocic/The Associated Press)

After all this, why am I grateful to da Vinci?

When I asked Dr. Corsten what the surgery would have looked like without da Vinci he replied, “In the good old days, we would have cut your jaw in two.” That’s how they got their access. The image of my jaw being split like a turkey wishbone was deeply unsettling. Radiation treatment has made even a simple tooth extraction impossible. The jaw won’t heal properly. Without da Vinci, I had no surgical option.

I have thanked all my doctors profusely. But I reserve a special thank you for da Vinci.

Domo arigato, Mr. Roboto.

About the author:

Glenn Deir is a retired CBC journalist and author.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.