Source: www.targetedonc.com

Author: Tony Berberabe, MPH

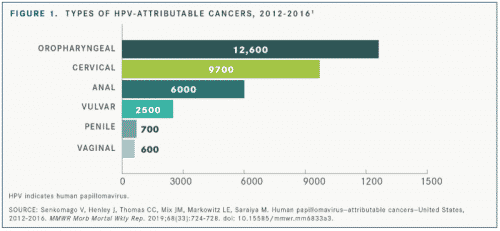

Although a vaccine for the human papillomavirus (HPV) is widely available, an average of 34,800 HPV-associated cancers attributable to the virus, including cervical, vaginal, vulva, penile, anal, and oropharynx were reported in the United States from 2012 through 2016, according to data published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.1 The estimated number of cancers attributable to HPV types targeted by the 9-valent HPV vaccine (9vHPV) is also rising. These recent increases are due in part to an aging and growing population and increases in oropharyngeal, anal, and vulvar cancers, lead author Virginia Senkomago, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist and senior service fellow at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, said in an email.

Although HPV vaccination is an important component of cancer prevention, only about 50% of adolescents have received the vaccine. Of cancer cases attributable to the HPV types targeted by the vaccine, 19,000 (59%) occurred in female patients and 13,100 (41%) occurred in male patients.

But there is some good news.

Senkomago said HPV infections and cervical precancers have dropped significantly since the vaccine was introduced. Infections with HPV types have dropped 86% among teenage girls. Among vaccinated women aged 20 to 24 years, the percentage of cervical precancers caused by the HPV types most often linked to cervical cancer dropped by 40%. The vaccination is recommended through age 26 for all individuals, especially for those who were not vaccinated when they were younger. The vaccine is not recommended for individuals older than 26 years, but some adults between 27 and 45 years may decide to get the HPV vaccine based on a discussion with their clinician. HPV vaccination provides less benefit to adults in this age range, as more have already been exposed to HPV, said Senkomago.

Further, it is anticipated that compliance should increase because the original 3 doses every 2 months now seems to be getting replaced by 2 doses with similar efficacy rates.

Previous annual estimates of cancers attributable to the types targeted by 9vHPV were 28,500 (2008-2012),2 30,000 (2010-2014),3 and 31,200 (2011-2015).4

“HPV is a distinct subset of head and neck cancers. It now exceeds cervical cancer as a major health burden in the [United States] because, in part, there’s no effective screening strategy,” said Robert L. Ferris, MD, PhD, director of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and co–physician editor in chief of Targeted Therapies in Oncology. A number of challenges exist in the treatment of patients with HPV-positive head and neck cancer, Ferris said. These include lack of a screening tool and relatively low adherence to vaccination. The disease also has a long latency period,5 adding to the difficulty in treatment.

“These patients don’t have traditional risk factors,” Ferris continued. “They may just present to their doctor with a lump in the neck area with very few symptoms. They usually have no history of tobacco use or exposure history, so they can be overlooked for weeks and months before a needle biopsy is ordered. Needle biopsy can be diagnostic.”

Of the 32,100 HPV cancer types, those with the highest incidence were oropharyngeal and the lowest was vaginal (FIGURE 1), the report said.1

“We are striving to vaccinate as many people as possible. Right now our goals are identifying groups with the lower rates, such as people who live in rural areas, and working to remove unique barriers to vaccination they may face,” Senkomago said.

Senkomago added that the most surprising finding was that oropharyngeal cancer was the most common cancer attributable to HPV types targeted by 9vHPV in most states, except in Texas, where cervical cancer was most common, and in Alaska, New Mexico, New York, and Washington DC, where estimates of oropharyngeal and cervical cancers attributable to the 9vHPV-targeted types were the same (FIGURE 2).1

In particular, Senkomago said, these findings can inform community oncologists of the burden of HPV-associated cancers, especially in light of the increase of cases of oropharyngeal, anal, and vulvar cancers. Increasing awareness of the burden of the 7 HPV-associated cancers, individually and as a group, is a powerful prevention tool. Oncologists can advocate for strategies such as screening and HPV vaccination. In addition, community oncologists can work together with cancer survivors to engage communities to vaccinate and get screened as appropriate, she said.

Ferris cautioned against changing treatment algorithms too soon, especially before prospective clinical trials result are fully analyzed. “We need specific clinical trials before we can reduce the intensity of therapy because we don’t want to impair the very good survival, which can be 80% to 90%, in these patients and put that at risk,” he said. “We don’t want to jeopardize that strong survival rate. Those prospective clinical trials are ongoing, and those results should be reported out intensively in 2020, 2021, and beyond.”

Although the report focused on only the 9vHPV vaccine, a quadrivalent vaccine is also available. Investigators are evaluating whether any shift in the subtypes of HPV that cause cervical or head and neck cancer has been detected with the implementation of the quadrivalent vaccine. Senkomago said scientists continue to evaluate HPV types before and after vaccine introduction in population-based studies. To date, they have not found any evidence that type replacement is occurring.6

References:

1. Senkomago V, Henley J, Thomas CC, Mix JM, Markowitz LE, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus—attributable cancers—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(33):724-728. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a3.

2. Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus–associated cancers — United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661-666. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a1

3. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus, United States—2010–2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no1-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2010-2014.htm. Accessed September 12, 2019.

4. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus, United States—2011–2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no4-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2011-2015.htm. Accessed September 12, 2019.

5. Human papillomavirus (HPV). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. cdc.gov/hpv/parents/cancer.html. Accessed September 10, 2019.

6. Mesher D, Soldan K, Lehtinen M, et al. Population-level effects of human papillomavirus vaccination programs on infections with nonvaccine genotypes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(10):1732-1740. doi: 10.3201/eid2210.160675.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.