Source: newatlas.com

Author: Paul McClure

A new study has uncovered how the commonly used local anesthetic drug, lidocaine, activates bitter taste receptors to exert an anti-cancer effect in head and neck cancers. Given its low cost and ready availability, the drug could easily be incorporated into the treatment of patients with this challenging form of cancer.

Anyone who’s had a cut sutured up or a dental procedure such as a filling will probably be familiar with lidocaine (also known as lignocaine). While it’s known how the local anesthetic drug exerts its pain-inhibiting effects, it’s been suggested that lidocaine also has a beneficial effect on cancer patients, although how is not fully understood.

Now, a study led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine has solved a long-standing mystery of how lidocaine causes the death of certain cancer cells.

“We’ve been following this line of research for years but were surprised to find that lidocaine targets the one receptor that happened to be mostly highly expressed across cancers,” said Robert Lee, a corresponding author of the study.

That ‘one receptor’ is T2R14, a bitter taste receptor that’s expressed in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), cancers with a high mortality and significant treatment-related morbidity. HNSCCs arise in the mucosa of oral and nasal cavities due to exposure to environmental carcinogens and/or the human papillomavirus (HPV).

In addition to their role in bitter taste perception, bitter taste receptors (T2Rs) are involved in innate immunity, thyroid function, cardiac physiology, and other biological processes. T2Rs have been studied in ovarian, breast, and HNSCCs, with T2R14 being the most well-studied.

The researchers had previously found that T2Rs were found in many oral and throat cancers, where they trigger apoptosis or programmed cell death, and that increased expression of T2Rs correlated with improved survival outcomes in patients with HNSCCs. And a study published earlier this year found that breast cancer survival increased when lidocaine was injected around the tumor before surgery.

“T2R14 is found in cells throughout the body. What’s incredibly exciting is that a lot of existing drugs activate it, so there could be additional opportunities to think about repurposing other drugs that could safely target this receptor.”

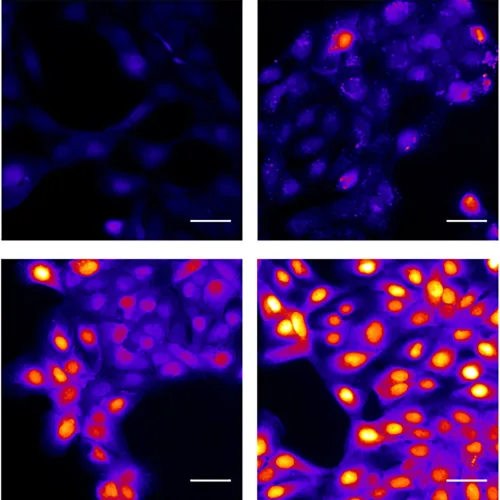

Using cell lines of HNSCCs, the researchers found that lidocaine activated the T2R14 receptor, leading to apoptosis of the cancer cells. Specifically, activation by the drug caused mitochondrial calcium overload, depolarizing the mitochondrial membrane and significantly decreasing HNSCC cell viability. It also caused the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), further indicating mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular stress.

Calcium responses to different concentrations of lidocaine in head and neck cancer cells. University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Their data also suggested that lidocaine inhibited proteasomal degradation. The proteasome rids the cell of thousands of short-lived, damaged, misfolded, or otherwise obsolete proteins. When proteasomal activity is inhibited, proteins meant for degradation accumulate, which can induce apoptosis. Lidocaine-induced proteasome inhibition was reversed when either ROS generation or T2R14 signaling was inhibited, suggesting that proteasome inhibition resulted from T2R stimulation, downstream mitochondrial dysfunction, and ROS.

An advantage, so to speak, of HNSCCs is that the affected sites are easily accessible so that lidocaine could be implemented into clinical practice as an injectable or topical anticancer treatment.

“Speaking as a head and neck surgeon, we use lidocaine all the time,” said Ryan Carey, co-corresponding author. “We know lidocaine is safe, we’re comfortable using it, and it’s readily available, which means it could be incorporated into other aspects of head and neck cancer care fairly seamlessly.”

The study also revealed that T2R14 was particularly elevated in HNSCCs associated with HPV, now the dominant form of HNSCC. A clinical trial is planned to test the addition of lidocaine to standard care for HPV-associated HNSCCs.

“While we’re not suggesting that lidocaine could cure cancer, we’re galvanized by the possibility that it could get an edge on head and neck cancer treatment and move the dial forward, in terms of improving treatment options for patients with this challenging form of cancer,” Carey said.

Note:

The study was published in the journal Cell Reports.

Source: University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.