Source: www.artsy.net

Author: Ryan Leahey

In a Baltimore basement, behind foot-thick walls, there is a room, and in that room there is a table. Every morning, Monday through Friday for seven weeks, my dad entered the room at 7:40 a.m. sharp. I accompanied him there on a few occasions, sitting outside in the waiting room as the door closed behind him. A minute or two would pass, followed by a barely audible buzz, then the door would slide open again and he’d walk out, another radiation treatment X’d off the calendar.

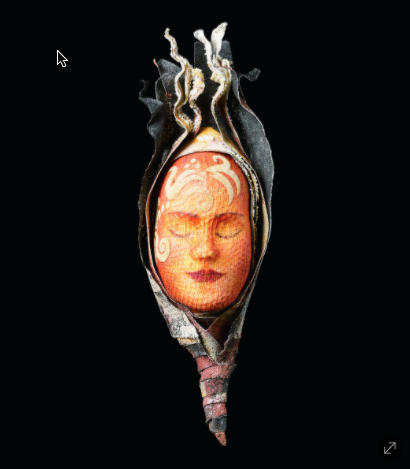

My dad’s experience in that room, one of many in the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, will be familiar to other throat cancer patients. A radiation technician bolted him down to the table with the help of a white mesh mask perfectly molded to the contours of his face. Wrapped tightly around his head and neck, the bizarre-looking armature ensured that powerful radiation beams targeted his cancer in the exact same position each session, even as his skin deteriorated and his body mass dropped.

Before his first treatment, he had been measured and fitted for his own custom mask. Plastic mesh was draped over his face until it hardened, forming a new face—what some patients call their second skin. For my dad, the object came to symbolize something, just as it symbolizes something for me, our family, and for the countless other people who have survived or helped someone survive head and neck cancer, or HNC.

My dad isn’t exactly the sentimental type, but on his last day of radiation, he rang the bell—a rite of passage for patients who make it through treatment—put the mask in his car trunk, and took it home.

Just as cancers and treatments are unique, however, the meaning of the mask is unique to every patient and to every person who comes into contact with it. Among those searching for that meaning are hundreds of artists, some of them survivors themselves, who have transformed radiation masks into works of art that seek to capture, or at least confront, the struggle and, for the lucky ones, the survival of HNC.

Groups across the U.S. and other parts of the world have come together to create new lives for these masks. One such group, Courage Unmasked, has, through a series of auctions and books, shown off an incredible array of masks, all while raising awareness of HNC and funds for patients in need.

Courage Unmasked is the brainchild of Cookie Kerxton, an artist and HNC survivor. In 2009, Kerxton felt lucky. She was fortunate to have had the finances and good health to survive her radiation treatment for cancer of the vocal cords. As Kerxton convalesced, she realized that not everyone is quite so lucky. Some HNC patients face a permanent loss of saliva, destroyed taste buds, digestive issues, and an inability to talk, eat, swallow, or breathe. And when it comes to the cost of covering incidentals like specialty foods, commuting, and the many small but crucial steps toward recovery, health insurance is often insufficient.

Kerxton had an idea. She inquired at the treatment center about the leftover radiation masks, the ghostly white shells of former patients. With permission from the center’s radiation therapists, she took home the discarded masks and called upon her artist friends to help transform them into works of art. She then auctioned off the finished objects, using the proceeds to support HNC patients by sending applicants a $500 check through a Maryland-based nonprofit called 9114HNC (Help for Head and Neck Cancer).

Since the first Courage Unmasked event in 2009, held at American University’s Katzen Arts Center in Washington, D.C.—which featured 108 masks, decorated by more than 100 artists—other such events have followed, each raising more money for 9114HNC.

Carol Kanga, an artist and HNC survivor, co-chaired the inaugural Courage Unmasked event and created a mask for the auction. “My attitude toward my mask was gratitude for the safety it represented,” she told me. “It meant precise treatment, the best available. When I walked into the radiation room and looked up at the shelves, scores of masks looked back at me. They signaled that I was not alone, that hundreds of people get through this, that each of us is a distinct individual receiving excellent treatment tailored exactly to each contour of our bodies.”

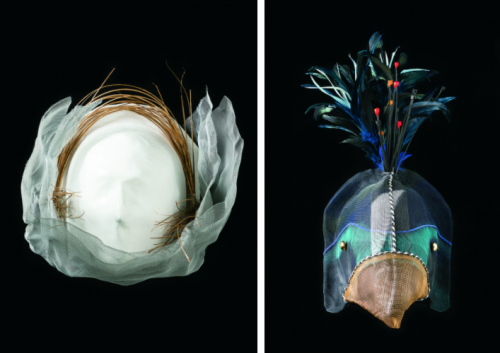

Her mask, she has said, “is designed to entice viewers to rejoice with me that life is and that we all are part of it.” And the range of other artist-adorned masks testifies to that life-affirming attitude. Some of the works are celebratory, like totemic symbols of victory over incalculable odds, while others are somber and severe, like fragile reminders of death. Flowers in bloom are a recurring theme, as are birds and their delicate, multicolored feathers.

Barbara Kerne created a mask inspired by Athena, the Greek goddess of arts and crafts who is said to have taken the form of an owl. Athena also happens to be the goddess of wisdom and strength, and thus, Kerne says, a symbol of “heroic endeavor and patron of those who need help.”

For artist Jeanne Heifetz, the mask, as an artifact of radiation, carried twin burdens of fear and hope. “I wanted to transform the emotional connotations of the mask, using alternative meanings of ‘radiation’ and ‘radiance,’” she says. Lacework and reflective copper turn the mask into what she calls a “protective armor for the wearer.”

Several artists sought to maintain the thread from mask wearer to mask reimagined. “This radiation mask came to me from a woman’s daughter in Colorado, who had tenderly sent it off in a box with pictures of mountains on it,” writes artist Anita Hinders in a catalogue that accompanied one Courage Unmasked event. “I think of this mask, Shades of Colorado, as a love letter continued.”

Allen Hirsch, a throat cancer survivor who recently became a board member for Courage Unmasked, hasn’t decided what to do with his mask just yet. “I have it in my living room,” he told me. “Each day I walk past the mask and it reminds me of the treatment experience and the other patients and family members I met at the radiation clinic and the infusion center. The mask is a reminder that life has changed.”

My dad hasn’t decided what to do with his mask, either. When I was home for the holidays, the mask was sitting on the dining room floor, our last name scrawled across the top. In unadorned white, it was bright like a halogen light. Later, I asked if he had any plans for it. He wasn’t sure. I showed him images of the artist-decorated masks in the Courage Unmasked catalogue, which he’d seen in the waiting room at Hopkins.

He liked some of the artwork, he told me, though he wasn’t too impressed by all the birds. He liked the stories, the book’s personal narratives from survivors and from artists trying to comprehend what he and others had been through, the most.

Dad was only a few days into radiation treatment when he first thumbed through the book at Hopkins, before he lost weight, his sense of taste, his hair, his voice. As those things come back to him, however slowly, he has come to appreciate those stories more. His trophy, as he calls his mask, is a symbol of his own story and how he was lucky, too.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.