Source: www.healio.com

Author: Drew Amorosi

Key takeaways:

- Researchers reported increased rates of antibiotic prescriptions in the 3 months prior to head/neck cancer diagnosis.

- Antibiotic prescriptions appeared linked to longer time between symptom onset and diagnosis.

Approximately 15% of individuals with head and neck cancer received an antibiotic prescription within 3 months of diagnosis, study results showed.

Those who received antibiotic prescriptions had significantly longer time to head and neck cancer diagnosis than those who did not receive antibiotics, findings published in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery showed.

“These patients have been through the health care system for many months without an accurate diagnosis,” Sean T. Massa, MD, assistant professor in the department of otolaryngology — head and neck surgery at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, told Healio.

“Prescribing antibiotics is a common practice and was associated with a delay in diagnosis,” he added. “For adults with a neck mass or swelling lasting more than 2 weeks, the most likely cause is a tumor, so patients should be evaluated through further testing and referral to a specialist.”

Background

Head and neck specialists have observed a steady stream of patients with neck masses mistakenly prescribed antibiotics because symptoms mirror that of infection, Massa said.

This occurs despite 2017 guidelines from American Academy of Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) for evaluation of neck mass among adults. The guidelines recommend against prescribing antibiotics without other infectious symptoms.

“We wanted to see if patients who received antibiotics took longer to get from a symptom diagnosis to a cancer diagnosis,” Massa said.

“We are concerned because we know that patients who wait weeks or months for a cancer diagnosis present at more advanced stages and require more aggressive treatments,” he added. “This results in a worse prognosis, costing more overall to the health care system while increasing morbidity.”

Methodology

Massa and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study to evaluate temporal trends and factors associated with time from symptom onset to prescribing of antibiotics prior to head and neck cancer diagnosis.

Researchers reviewed anonymized electronic health records from a data set of 7,811 individuals (mean age, 60.2 ± 15.8 years; 53% men; 78.6% white) diagnosed with head and neck cancer from 2011 through 2018.

The cohort included patients from 85 health care systems across all 50 states.

Researchers established antibiotic prescription within 3 months before head and neck cancer diagnosis as the study’s exposure of interest. Days from the first documented symptom to head and neck cancer diagnosis served as the study’s primary outcome.

Key findings

Results showed 1,219 patients (15.6%) received at least one antibiotic prescription within 3 months before head and neck cancer diagnosis. By comparison, 8.9% of patients received a prescription for an antibiotic during the study’s baseline period, from 12 months to 9 months before cancer diagnosis.

The rate of antibiotic prescribing within 3 months before cancer diagnosis did not change over time (quarterly percent change, 0.49%; 95% CI, 3.06% to 4.16%).

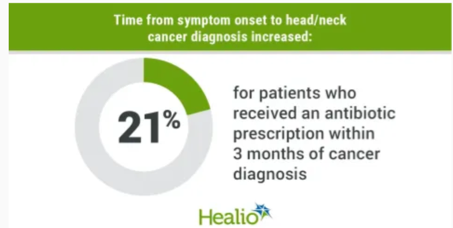

Patients who received an antibiotic prescription within 3 months of head and neck cancer diagnosis waited 21.1% longer between symptom onset and cancer diagnosis (adjusted rate ratio [RR] = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.14-1.29). The time between symptom onset and head and neck cancer diagnosis increased when including symptoms presenting within 6 months (adjusted RR = 1.38; 95%CI, 1.3-1.47) and 12 months (adjusted RR = 1.5; 95% CI, 1.42-1.6).

Compared with otolaryngologists, primary care/internal medicine physicians were more likely to prescribe antibiotics when a presenting symptom was documented (adjusted prevalence ratio = 1.6; 95% CI, 1.27-2.02).

Patients with symptoms in addition to neck mass or swelling had significantly longer time from symptom onset to head and neck cancer diagnosis (adjusted RR = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.08-1.59).

Researchers acknowledged study limitations, including the nonrandomized cohort and lack of detail about physicians’ rationale for prescribing antibiotics.

Clinical implications

The results showed no change over time in the proportion of individuals prescribed antibiotics in the months leading to a head and neck cancer diagnosis. This suggests AAO-HNS guidelines likely had “no measurable effect” on prescribing behavior during the study period, Massa said.

Although head and neck specialists are aware of the likelihood that a neck mass may be cancer, recommendations from the guidelines are not reaching frontline physicians — including primary and emergency care clinicians, he added.

“It’s incumbent upon us as head and neck specialists to do more than just put out guidelines,” he told Healio. “We also to reach out to other communities and specialty practices to help them understand the needs of the patients who will eventually end up in our care.”

Although outreach regarding diagnosis of neck masses among adults is a worthy goal, the volume of specialist guidelines makes it “impossible to expect primary care and urgent care clinicians to stay abreast of the interminable deluge of subspecialty guidelines,” Evan M. Graboyes, MD, MPH, of the department of otolaryngology–head & neck surgery at Medical University of South Carolina, and colleagues wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Graboyes and colleagues instead recommended the use of technology-based options to reduce head and neck cancer misdiagnosis, including artificial intelligence and other data-driven clinical decision support tools.

“Gallogly and colleagues have shown us that for many patients with head and neck cancer, the road from symptom onset to [cancer] diagnosis should be marked with a sign reading ‘Warning, Detour Ahead,’” Graboyes and colleagues wrote. “It is now incumbent on us to work in a collaborative and multidisciplinary fashion to create a road free of detours for our patients and ensure that these important findings are translated back to decrease morbidity and mortality.”

References:

Gallogly JA, et al. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2023.2423.

Graboyes EM, et al. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2023.2462.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.