Source: Targeted Oncology

Date: May 17th, 2020

Author: Tony Berberabe

De-escalating therapy has the potential to dramatically reshape the treatment of patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers, but only if a number of key trials come back with positive long-term data with 3 cycles of cisplatin at 100 mg/m2 times 3, given every 3 weeks, Sue Yom, MD, PhD, a professor in the Departments of Radiation Oncology and Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery atthe University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview with Targeted Therapies in Oncology (TTO).

Sure, there were some minor variations over the years, small alterations made on a case-by-case basis. “But long story short, that’s fundamentally what was happening: 70 Gy with 3 cycles of high-dose cisplatin,” Yom said. The story began to change a little over a decade ago, with the introduction of a variable that could potentially change the course of therapy for a large percentage of patients with head and neck cancers. Today, the operative word remains potentially.

In 2008, Maura L. Gillison, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, and colleagues found that whether head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumors were associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) turned out to be a major prognostic indicator.1

“When that finally came to be reported, there was a very, very striking result,” said Barbara Burtness, MD, a professor of medicine (medical oncology), Disease-Aligned Research Team leader of the Head and Neck Cancers Program, and coleader of Developmental Therapeutics at Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut Patients with HPV-associated stage III or IV head and neck squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx or larynx had a 2-year overall survival (OS) rate of 95% versus 62% for patients with HPV-negative tumors.

Two years later, Gillison collaborated with K. Kian Ang, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and published the results of a study in oropharyngeal cancer (NCT00047008), which again found that HPV made a difference in terms of survival.2

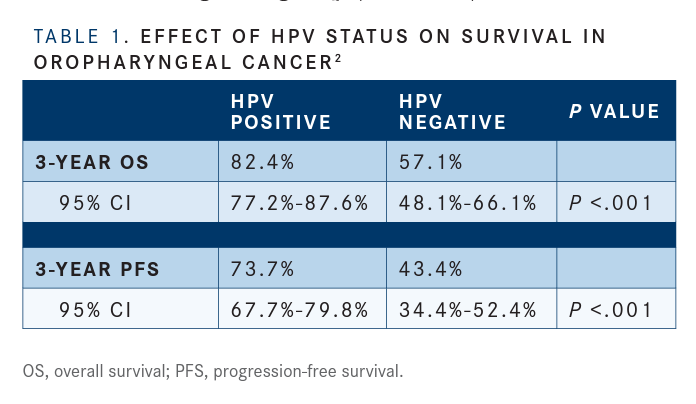

Patients with HPV-positive tumors had better OS and progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who were HPV negative (P<.001 for both comparisons). Ang and colleagues reported that the 3-year OS rate was 82.4% (95% CI, 77.2%-87.6%) in patients who were HPV positive compared with 57.1% (95% CI, 48.1%-66.1%) in those who were HPV negative. Similarly, the 3-year PFS rate favored the HPV-positive group, at 73.7% (95% CI, 67.7%-79.8%) versus 43.4% (95% CI, 34.4%-52.4%) for the HPV-negative group (TABLE 1).2

The 3-year absolute benefit of HPV-positive status for OS was 25% (95% CI, 11%-40%), and the absolute benefit for PFS was 30% (95% CI, 15%-45%).

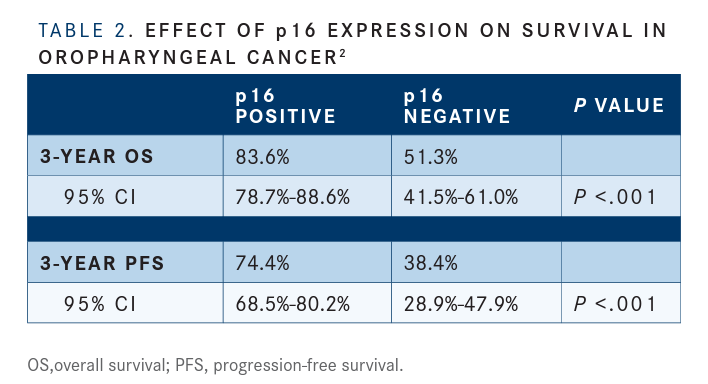

The results were similar with stratification according to p16 expression status. The 3-year rates of OS were 83.6% (95%CI,78.7%-88.6%) in the subgroup that was positive for p16 expression and 51.3% (95% CI, 41.5%-61.0%) in the subgroup that was negative (P<.001). Three-year PFS rates were 74.4% (95% CI, 68.5%-80.2%) and 38.4% (95% CI, 28.9%-47.9%), respectively (P<.001) (TABLE 2).

The study also found that the number of pack-years an individual smoked had a substantialnegative impact on prognosis.

These findings raised serious questions because the current standard of care, unchanged from that described by Yom, can have a profound effect on the life of a patient who survives the cancer. “The after- effects of that dose of radiation are quite real, and they include chronic pain, chronic swallowing difficulties, dry mouth, and dental complications,” Burtness said.

“We are concerned that these patients may be at higher risk for death from the late effects of the treatment.”

Moreover, patients with HPV-associated cancers tended to be younger at diagnosis than those with non-HPV cancers. Patients who develop the cancer in their 50s might have decades of life left—plenty of time for the long-term adverse effects (AEs) of aggressive treatment to show up.

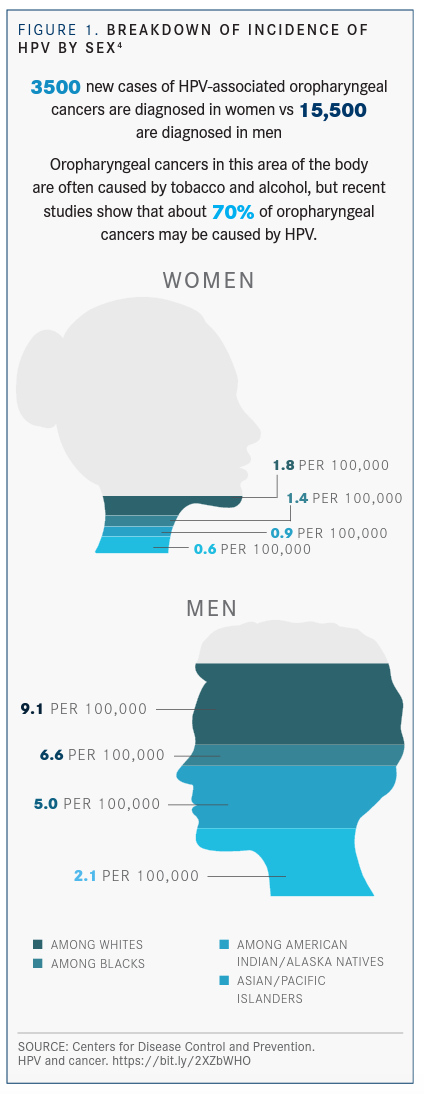

The issue is pressing because HPV-associated cancers represent about 7 in 10 cases of oropharyngeal cancer.3 The most recent statistics from the Centers for Diseases Control & Prevention suggests that 3500 new cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers are diagnosed in women versus 15,500 diagnosed in men (FIGURE 1).4

Cherie-Ann O. Nathan, MD, chairman of the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgeryat Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, said the new findings underscored the need for more research. “We need to start to look at de-escalating for that low-risk group,” she said.

De-escalation Strategies

Deciding that different strategies might be warranted and choosingwhich approaches make the most sense are 2 different considerations, and both come with difficult questions. Burtness said it can be a challenge just to figure out how to tackle the question.

I think, first of all, it’s challenging to do deintensification trials because they require very large sample sizes, and you want to be sure you’re not deintensifying [treatment in] somebody who would be cured by the full treatment and wouldn’t be cured by the reduced regimen,” Burtness said.

For the most fortunate patients, the OS rate with the current standard of care is in the range of 90% to 95%, setting a high bar for its replacement, Yom said. “It’s a huge ethical and practical situation where you’re actually having to estimate: ‘What would it take to prove that this less intense alternative was as good?’” Yom said.

“Patients do get better with time,” Yom said. “After a year or 2, they can live very normal lives.It’s actually a great treatment in some ways, and 1 question is if we should even be messing with it.”

Another strategy is to reduce the dose or field of radiation. In Yom’s much-anticipated trial, NRG-HN002 (NCT02254278), 306 patients with p16-positive, non–smoking-associated, locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal cancer were stratified by unilateral or bilateral radiation and randomized into 2 groups.4 One group received 60 Gy of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for 6 weeks plus cisplatin (IMRT + C) at 40 mg/m2 weekly. The other group received 60 Gy of modestly accelerated IMRT alone for 5 weeks. The goal was to compare the arms in terms of 2-year PFS rates without unacceptable swallowing difficulty at 1 year. The IMRT + C group met the desired benchmarks; the IMRT alone group did not.

Although the study was just a phase II trial, Yom said the results were encouraging and will lead to further study.

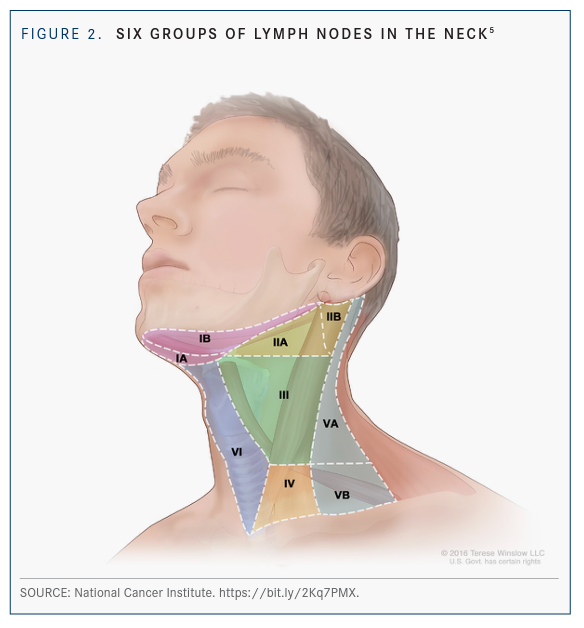

Another strategy is to perform surgery up front, Nathan said. If the margins are negative and there is not a significant number of metastatic lymph nodes or significant extranodal extension, chemotherapy might be avoided. She said transoral surgery has become much more effective and precise in the age of robotics. A common site of lymph node involvement is the retropharyngeal region, shown in FIGURE 2.5

“When robotic surgery became popular and we were able to get margins on these tumors at the base of [the] tongue and tonsils, people started saying [that] for the HPV-associated [tumors], you don’t need the typical wide margins of 5 mm; you could get away with 3 mm,” she said.“ So, the whole purpose of transoral surgery was that after removing the tumor, you could de-escalate.”

Other research has tested the replacement of cisplatin with cetuximab (Erbitux), though one study found that the latter resulted in inferior OS.6

With the exception of the cetuximab strategy, the novel approaches have shown promise. However, Nathan said, clinicians should realize that these are all still hypotheses; there is much that is not yet known.

“Unfortunately, people look at all [these] retrospective data and small institutional trials and make [treatment] decisions, not realizing that it’s still not standard of care,” Nathan said. “It’s fine to de-escalate, but always de-escalate if you can on a clinical trial.”

Ongoing Research

A number of important ongoing trials have the potential to add significant scientific rigor to the debate. Among them is Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group’s ECOG-E3311 trial (NCT01898494), which is examining transoral surgery followed by low- or standard-dose radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. Initial findings are expected to be presented at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting and the trial is expected to be completed in 2023. The PATHOS trial (NCT02215265), which is evaluating transoral resection followed by reduced-intensity radiotherapy with or without cisplatin, is expected to be completed in 2026.

Yom and colleagues are working on NRGHN005 (NCT03952585), a phase II/III study in which patients will undergo deintensified radiation therapy with cisplatin or the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo) versus standard-of-care chemoradiation. The investigators used an innovative design so that the study will produce scientifically rigorous results for the 70 Gy versus 60 Gy question at the phase III level, even if the nivolumab phase II investigation does not meet its targeted end points, Yom told TTO.

In the meantime, Burtness said, the data are beginning tosuggest, if not conclusively, which types of patients might be a good fit for deintensification. “The omission of chemotherapyin the postoperative setting after transoral resection is probably better for patients with smaller nodes, maybe only 1 or 2 nodes,” she said. “The use of more induction chemotherapy and a lesser dose of radiation is better, obviously,for patients who are going to tolerate chemotherapy well. The omission of systemic chemotherapy and the use of immunotherapy may eventually [lead to the development of] a biomarker signature.”

She cautioned that it is not clear that all HPV-associated cancers should be treated the same way. Certain other factors appear to affect the opportunity for deintensification. “Repeatedly, we’ve seen [that] patients with T4 cancers don’t do well with deintensification,” she said. “Patients who’ve smoked more than 10 pack-years won’t do well.”

Burtness added that there is a good chance the end result of all the research will simply be that certain deintensification strategies are better for certain patient populations. Yom agreed. “One of our goals is to make deintensification acceptable within the standard of care,” she said. “But I’m not sure there’s going to be just 1 standard of care going forward.”

Even if these new strategies show equal or better success rates compared with the current standard ofcare, patients who undergo deintensified therapy might avoid the toxicities of more intense therapy at the cost of unexpected long-term AEs.

The 2 key takeaways from the study we put together are that, 1, there are a lot of different deintensification strategies, and in the short term, a lot of these different strategies don’t show any differences in outcomes or toxicity,” Patel said. “But the second point that is crucial is that longer-term follow-up is necessary for making judgments as to whether or not to do deintensified treatments.”

Nathan said 1 major concern is that patients with deintensified treatment regimens might facea higher risk of a subsequent cancer diagnosis. “HPV- associated cancers still have the same distant metastasis rate as HPV-negative cancers,” she said. “And the distant metastasis is occurring years later and sometimes in unusual locations.”

For example, lack of systemic therapy might not affect the current oropharyngeal tumor, but years later, could it lead to a cancer that might have been prevented? That type of question is impossible to answer at thispoint, andNathan says it is problematic to assume the answer is no.

Nathan also raised concerns about changes to the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) staging system. In the eighth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, HPV-associated cancers were restaged because staging is generally meant to match prognoses, and HPV-associated cancers had been shown to have better prognoses, she said.The end result of the restaging, she said, is that some cancers previously deemed stage IV might now be reclassified as stage I or II. Nathan worries that the lower staging will result in even more deintensification because clinicians will not consider cases as serious as they once did, which would be a mistake, she said. “All the patients who did so well and have such good survival [in the existing de-escalation literature] were being treated like they were stage III or IV,” she said. “So, until you have the results of [ongoing clinical trials], you shouldn’t be doing it.”

Deintensification Today

Clearly, some level of deintensification is occurring withinclinics inthe United States.If itturnsout that 1 or more of the new, lower-intensity strategies is effective, the treatment paradigm for patients will be drastically different, Yom said:“To start talking about things like patient preferences and quality of life is foreign and different in oropharyngeal cancer.”

Patient preference is a key consideration,Patel said: “That’s why the data and being able to share with patients that these outcomes aren’t different at longer-term follow-ups is important.”

Different types of patients will likely favor different approaches, even if de-escalation is validated as a standard option, according to Yom. “I have patients who come to my clinic, and they’re like, ‘I have 2 kids. I’m staying alive. Hit me with everything you have,’” she said.

A large spectrum of Yom’s patient population is very highly educated about their cancers, she said, and that knowledge can inform the strategies they prefer. In many cases, education leads patients to be less concerned about mortality and more concerned about the impact of therapy on quality of life.

“There’s a large proportion of that population where their driving concern is this fear of long-term consequences,” she said.

Yom said radiation oncologists will need to better help patients, who until now had few treatment choices, think through their options. “We don’t have good structures and instruments to help people sort through the decision-making process ina way that makes sense to them,” she said. “I don’t think anybody does.”

Even if the data from the current trialsare positive, Nathan cautioned, the time horizon to evaluate outcomes must be longer than a few years. “Most of these trials are looking good, but follow-up is only about 3 to 4 years, she said. “A lot of our toxicities [that we have seen] have occurred 5 and 8 years later.”

That will require oncologists to be involved in decisions that might be thornier than those patients previously faced. “You’re going to have to be a much better oncologist,” Yom said.

Still, she and others say the challenge will be well worth it, but only if the ongoing scientific study findings support the optimism now shared by many in the field. “This deintensification movement will have huge implications [for] how the majority of patients with head and neck cancers will be treated in this country going forward,” Yom said.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.