Source: www.iflscience.com

Author: Rosie McCall

Scientists have analyzed the genomes of viruses to reveal the surprisingly complex evolutionary past of the human papillomavirus (HPV), exposing the salacious details of our ancestors’ sexual history in the process.

HPV comes in several flavors but HPV16 is the most common subtype worldwide – and it is the one most frequently identified in cervical cancer. Together HPV16 and HPV18 are responsible for 70 percent of all cases, accord to stats from the World Health Organization (WHO).

The problem is, it isn’t exactly clear how HPV strains contribute to cervical cancer (and other types, including cancer of the anus, the throat, the base of the tongue, and the tonsils). Or why the virus naturally clears in some people but not others. Researchers hope that studying the evolution of the virus will expose biological insights and point at mechanisms that might explain how cervical cancer develops.

To try to untangle HPV16’s thorny evolutionary past, scientists led by the Chinese University of Hong Kong isolated and examined oral, perianal, and genital samples in 10 adult female squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) and eight adult rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), half of whom were male and half of whom were female.

They found that the virus strains with most in common came from the same part of the body – meaning the oral samples from the squirrel monkeys and rhesus monkeys had more in common than oral and genital samples from the same species, for example. This, the authors say, implies the viruses adapted to a specific body part (or niche) where they co-evolved with their host for millions of years before passing to humans.

For the next part of the study, published in the journal PLOS Pathogens, the researchers compared 212 complete HPV16 virus genomes and 3,582 partial sequences to find out when exactly the HPV16 variants A, B, C, and D diverged from one another.

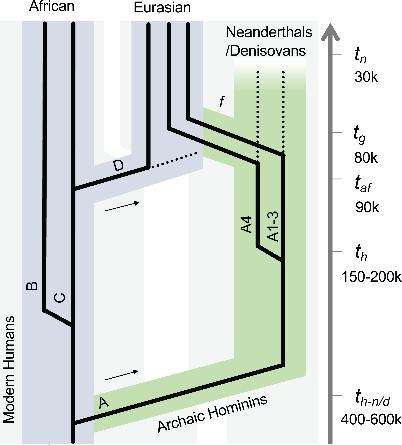

Previous studies have shown that one (the HPV16 A variant) was a lover’s gift from our hominid relatives, the Neanderthals, transmitted to modern humans after a few too many nights of interspecies shagging. Now, it looks like this particular variant split from the virus’ “family tree”, setting off its own trajectory, just as modern humans and archaic hominins (Neanderthals and Denisovans) parted ways, evolutionarily speaking, 618,000 or so years ago.

While the HPV16 A variant co-evolved with its Neanderthal and Denisovan hosts, HPV16 B and HPV16 C variants co-evolved with modern humans. The different strains remained in their respective hosts for hundreds of thousands of years, the study authors say. Then, 100,000 years ago or thereabouts, a small band of Homo sapiens ventured outside of Africa and into Eurasia where they met – and intermingled – with other hominin species, contracting certain HPV16 A variants in the process.

The consequences of this can still be seen today and can help explain why certain variants are more commonly seen in certain groups, the HPV16 A variant in Europeans and Asians, for instance. Hopefully, the authors say, this new information will improve our understanding of why some variants of HPV16 may be inherently more carcinogenic than others.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.