Source: online.wsj.com

Author: Kevin Helliker

About 18 months ago, Russell Stevens gave up cigarettes and took up a new habit — placing between his lip and gum a tiny pouch of smokeless tobacco called Camel Snus. The 26-year-old Kentuckian says it satisfies his craving for nicotine while exposing him to far fewer risks than did smoking.

Like Mr. Stevens, more Americans are continuing to give up smoking, helping to push cigarette consumption down about 3% each year. To help kick the habit, many smokers turn to safer sources of nicotine — the addictive but non-carcinogenic ingredient in cigarettes — such as nicotine gum, patches or lozenges.

But one method that has been gaining ground as a safer alternative to cigarettes — smokeless tobacco — remains controversial. A decades-old federal law requires smokeless tobacco to carry a label warning that it is not a safe alternative to cigarettes. The perils include possibly increased risk for certain cancers and cardiovascular disease. And U.S. public-health officials note that no clinical trials have been conducted showing that smokeless tobacco is an effective quitting aid. Adding to the controversy: Some of the biggest cigarette makers are jumping into the non-combustible market.

“There is no evidence that smokers will switch to smokeless tobacco products and give up smoking,” Michael Thun, vice president of epidemiology for the American Cancer Society, said in a recent article in the journal CA.

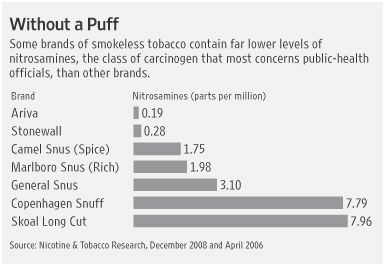

Still, popular brands of smokeless tobacco generally contain far fewer carcinogens than do cigarettes, although some studies indicate the habit isn’t risk-free. One recent study showed that some newer brands, with names like Ariva, Camel Snus and Marlboro Snus, have sharply lower levels of a dangerous carcinogen than do older varieties of smokeless tobacco, such as Copenhagen and Skoal. Britain’s Royal College of Physicians, which sets health standards in the United Kingdom, has said smokeless tobacco is between one-tenth and one-one thousandth as hazardous as smoking, depending on the specific product. As with all nicotine-replacement products, smokeless tobacco can lead to addiction.

Morgan Stanley estimates that U.S. consumers spent $4.77 billion on smokeless tobacco in 2007 versus $78 billion on cigarettes. Smokeless-tobacco sales have been increasing about 5% or more a year.

Some switchers say the benefits of smokeless tobacco can be immediate and dramatic. After 30 years of smoking more than a pack a day, Deborah Barr required several respiratory medications just to breathe. An analysis of her lung capacity shocked her physician. “He said, ‘I’ve never seen anybody this bad,’ ” recalls Mrs. Barr, 53, of Richmond, Va. So she switched to Ariva, a tobacco pellet that dissolves in the mouth. “Within three days I could breathe without medication,” says Mrs. Barr, who smoked her last cigarette four years ago and still uses Ariva.

No Spitting

For many people, smokeless tobacco conjures up an image of a wad of chewing tobacco bulging from the cheeks of users who spit brown juice. Instead, recent products consist of dissolvable pellets or tiny pouches of tobacco that reside invisibly in the mouth and induce no spitting. The model for these new brands comes from Sweden, where use of spit-free smokeless tobacco, called snus, is more common among men than smoking.

Studies of Swedish snus users have found no elevated incidence of mouth cancer compared with the general population. Other studies, however, have linked snus consumption to cardiovascular disease, albeit at rates far below the risks of smoking, and some research has found a minor link with pancreatic cancer. Many of the studies were performed by the Swedish government, which discourages the use of snus and cigarettes.

Big U.S. cigarette makers have been staking out the smokeless tobacco field. Altria Group Inc., the nation’s largest cigarette maker, this month completed its $10.3 billion purchase of UST Inc., the biggest smokeless-tobacco maker and owner of the Copenhagen and Skoal brands. Reynolds American Inc., which owns Conwood Co., a discount smokeless purveyor, this month announced that the Camel Snus brand has performed well enough in test markets to warrant national distribution. Marlboro Snus is available in a few test markets.

“There are probably in excess of 400,000 adults switching to smokeless each year,” says Seth Moskowitz, a spokesman for Reynolds American. But the company doesn’t know whether switchers succeeded in permanently giving up their previous form of tobacco.

Tommy Payne, Reynolds American’s executive vice president of public affairs, says that he himself is a Camel Snus user. When asked, he says the product helped him successfully quit smoking, a habit he says he had practiced for “too long.”

Cutting Nitrosamines

A federally funded study by the University of Minnesota’s Masonic Cancer Center found that Camel Snus, made by Reynolds American unit R.J. Reynolds, and Marlboro Snus, made by Altria’s Philip Morris unit, bear substantially lower levels of nitrosamines, the class of carcinogen that most concerns public-health officials, than do traditional brands. The study, published in the December issue of Nicotine & Tobacco Research, a leading journal of researchers battling tobacco-caused disease, was similar to one done in 2006 measuring the carcinogen in Ariva and Stonewall, two smokeless-tobacco products made by tiny Star Scientific Inc.

“The reduction in carcinogenic…content in the new smokeless tobacco is encouraging,” concluded the authors, none of whom had financial ties to industry.

The December study also found that Marlboro Snus contained a very low level of nicotine. By contrast, Camel Snus offers a jolt of nicotine that “has the potential to satisfy those smokers who are looking for a substitute to smoking, and to keep them addicted to this product,” the authors said.

An Altria spokesman says the nicotine level of Marlboro Snus has been increased. “Our interest is offering Marlboro Snus to adult smokers who are interested in a smokeless alternative to cigarettes,” the spokesman says.

Purveyors of smokeless tobacco aren’t marketing it as a smoking-cessation aid, because doing so could force it off the shelves as an unapproved medical treatment. Makers of the products are beginning to push back against such limitations, although they haven’t yet altered their marketing pitches.

Star Scientific this month announced that a study it conducted of smokers in withdrawal found that its Stonewall smokeless tobacco and a nicotine lozenge, used separately, proved to be “much more effective” than placebos at satisfying cravings. And Reynolds American is calling for public-health officials to talk openly about the lower risks of non-combustible tobacco products. “I believe that governments, public-health associations, tobacco manufacturers and others should provide consumers with accurate information, based on sound science, on the different levels of risks posed by different types of tobacco products,” Susan Ivey, chairman of Reynolds American, said in a speech last year at the University of Arkansas.

Some smokers on their own have long viewed smokeless tobacco as a way out of their habit. During medical school in the early 1970s, Michael Moore was trying without luck to kick cigarettes when a fellow nicotine addict recommended that he switch to smokeless tobacco. The Minneapolis resident stopped smoking and used smokeless tobacco for decades, quitting two years ago at the urging of his loved ones. “I never saw anything in the scientific literature that convinced me it was very dangerous,” says Dr. Moore. As a psychiatrist, however, he concedes that rationalization is a symptom of addiction. Dr. Moore says he has no connection to anti-tobacco causes, although his father, a scientist, years ago contributed to research linking cigarettes to disease.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.