Source: www.popsci.com

Author: Jeremy Hsu

And cigarette smokers get a free mutation in every pack

In a major step toward understanding cancer, one of the biggest problems bedeviling modern medicine, scientists have now cracked the genetic code for two of the most common cancers. This marks just the beginning of an international effort to catalog all the genes that go wrong among the many types of human cancer, the BBC reports.

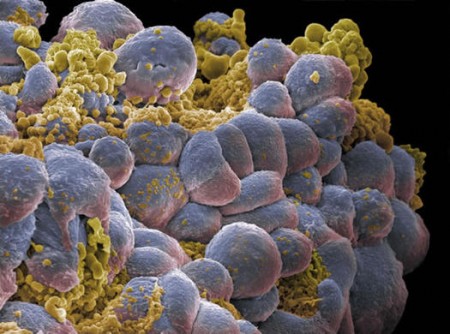

- Cracking the Cancer Code A cluster of breast cancer cells, with blue ones marking actively growing cells and yellow marking dying cells. Could scientists crack their code next?

Too much time spent under the sun apparently leads to most of the 30,000 mutations contained within the DNA code for melanoma, or skin cancer. Outside experts told the BBC that no previous study has managed to link specific mutations to their causes.

Wellcome Trust scientists also found more than 23,000 errors in the lung cancer DNA code, with most caused by cigarette smoke exposure. A typical smoker might get one new mutation, possibly harmless but also possibly a cancer trigger, for every 15 cigarettes that they smoke.

The new cancer maps could lead to better blood tests for diagnosing the respective cancers, as well as better targeted drugs. Blood tests might even reveal the DNA patterns that suggest cancer lies on the horizon.

The International Cancer Genome Consortium still expects to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars in cracking the code of the many human cancers. The U.S. has the job of studying cancers of the brain, ovary and pancreas, while the UK examines breast cancer. China is tasked with decoding stomach cancer, Japan is focused on liver cancer, and India has taken a crack at mouth cancer.

This painstaking research can only help futuristic treatment efforts, such as nanoparticle-targeted lasers and do-it-all nanoparticles that can track, tag and kill cancer cells. But those cancer-resistant mole rats should still count their lucky stars.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.