Source: physicsworld.com

Author: Jigar Dubal

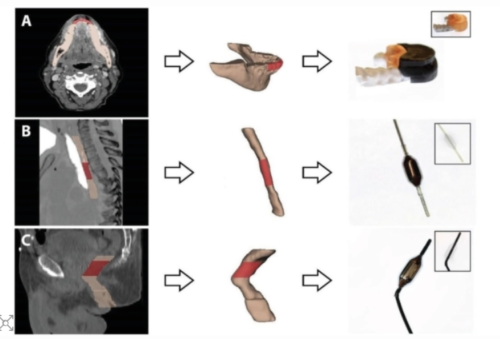

Personalized 3D-printed devices for radioprotection of anatomical sites at high risk of radiation toxicity: intra-oral device (A), oesophageal device (B) and rectal device (C) generated from patient CT images. The area for protection is highlighted in red. (Courtesy: CC BY 4.0/Adv. Sci. 10.1002/advs.202100510)

One of the primary goals of radiation therapy is to deliver a large radiation dose to cancer cells whilst minimizing normal tissue toxicity. However, most cancer patients undergoing such treatments are likely to experience some side effects caused by irradiation of healthy tissue. The extent of this damage is dependent on the treatment location, with the most common toxicities involving the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract.

Materials with a high atomic number (Z), often known as radiation-attenuating materials, can be used to shield normal tissue from radiation. However, integrating such materials into current patient treatment protocols has proven difficult due to the inability to rapidly create personalized shielding devices.

James Byrne and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital and MIT have addressed this need. The team has developed 3D-printed radiation shields, based on patient CT scans, incorporating radiation-attenuating materials to reduce the toxicity to healthy tissue.

Producing personalized 3D-printed shielding

Before a patient undergoes radiotherapy, they undergo CT scans to provide anatomical information that is used to plan their treatment. Byrne and his colleagues utilize these CT images to design personalized radio-protective devices, which they produce through 3D printing.

To determine the most appropriate shielding materials for the device, the researchers tested various elements and alloys, including liquids, with a high Z number. They characterized these materials by measuring their relative mass attenuation coefficients. From this, the team determined that elemental materials demonstrated greater radiation shielding than alloys or composites, and that mercury largely outperformed all other liquids. They then incorporated the high-Z materials into the personalized 3D-printed devices. The devices were made such that the shielding material could be removed to reduce artefacts during CT imaging and replaced prior to treatment.

To evaluate the device’s ability to shield healthy tissue from radiation, the team treated 14 rats with single-dose irradiation, half with and half without radio-protective devices in place, and examined the incidence of toxicities such as oral mucositis and proctitis.

The group also simulated clinical radiation treatments by modelling the radio-protective devices in the treatment planning software. The dose distributions with and without shielding were compared to evaluate the dosimetric impact of the device. The researchers simulated treatments of prostate and head-and-neck cancer patients, selecting the appropriate positioning of the device based on the regions of increased radiation exposure.

Evaluation of radio-protective devices

Histopathological analysis revealed that only one of seven rats with radio-protective devices in place during treatment suffered ulceration on the surface of the tongue. In contrast, all seven control rats, with no device in place, experienced extensive ulcerations on the tongue surface.

The clinical simulations identified that using radio-protective devices during prostate cancer treatment could reduce the dose to healthy tissue by 15% without reducing the dose delivered to the tumour. For the head-and-neck cancer treatment, the dose absorbed by inner-cheek tissue was reduced by 30%.

The results clearly show that the radio-protective devices may improve patient comfort throughout the course of treatment. “Our results support the feasibility of personalized devices for reduction of radiation dose and associated side effects” claims Byrne.

Future clinical implementation

The benefits of using 3D-printed radio-protective devices in the clinic are clear. “This personalized approach could be applicable to a variety of cancers that respond to radiation therapy,” says Byrne.

The researchers acknowledge that full clinical translation of 3D-printed shielding devices will require further development. “Given the small sample size of our dosimetric studies, further investigation in larger cohorts is needed to validate these approaches,” they say.

The researchers publish their findings in Advanced Science.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.