Hardly a day goes by when some news outlet does not report, often breathlessly, some new breakthrough in cancer research. We need to turn a skeptical eye on most of these reports, particularly those that contain information about very preliminary research findings. The always astute Gary Schweitzer gives a good perspective on this in his HealthNewsReview.org; it’s a good site to bookmark if you follow the medical news.

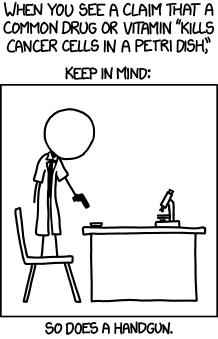

The key thing to remember is that many, many substances have been found to attack and kill cancer cells in the laboratory. The cartoon above, from the wonderful site xkcd, illustrates the problem. This is generally how promising anti-cancer agents are first identified: we test them against cancer cells growing in a dish. These are called in vitro (“in glass”) studies. But once a potential cancer treatment is found there is a long way to go. First of all, can the concentrations of the agent that showed cancer-killing activity in the dish be safely achieved in the body? And, if they can, does the agent still show that ability in the incredibly complex system of the body? Often such in vivo (“in life”) studies are first done in experimental animals before they are tried in humans.

The testing process in humans is long and complicated. By convention it is divided into several phases. These are worth knowing about because the media will often enthusiastically report results from phase I trials, which represent very preliminary findings. Here are the phases and what they mean:

• Phase I trials: Researchers test a new drug or treatment in a small group of people for the first time to evaluate its safety, determine a safe dosage range, and identify side effects.

• Phase II trials: The drug or treatment is given to a larger group of people to see if it is effective and to further evaluate its safety.

• Phase III trials: The drug or treatment is given to large groups of people to confirm its effectiveness, monitor side effects, compare it to commonly used treatments, and collect information that will allow the drug or treatment to be used safely.

There are also what are called Phase IV trials. These are important, too. They monitor what happens with the drug after it is released by the FDA for clinical use following successful Phase III trials. It is not uncommon for problems to be noticed after it has been used for a while, primarily because now there is a larger group of people getting it than were included in the Phase III trials.

So when you read about some new cancer breakthrough, check to see if these results are in vitro studies, animal studies, or early (i.e. before Phase III) trials in humans. Cancer treatment advances are big news, and the media tends to hype them quite a bit. The medical researchers themselves are often guilty of this, too, which is understandable — all of us would like discoveries we make to be ground-breaking.

If you are interested in more detail about how clinical trials work you can find it at the National Institutes of Health.

Christopher Johnson is a pediatric intensive care physician and author of Your Critically Ill Child: Life and Death Choices Parents Must Face, How to Talk to Your Child’s Doctor: A Handbook for Parents, and How Your Child Heals: An Inside Look At Common Childhood Ailments. He blogs at his self-titled site, Christopher Johnson, MD.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.