- 6/17/2007

- web-based article

- John Spangler M.D.

- ABC News (www.abcnews.go.com)

Stop smoking by using smokeless tobacco?

Except for a very vocal minority of tobacco experts, most tobacco researchers would not recommend this.

Nonetheless, with the blessing of this vocal minority, this is exactly what tobacco giant Philip Morris intends to do in August.

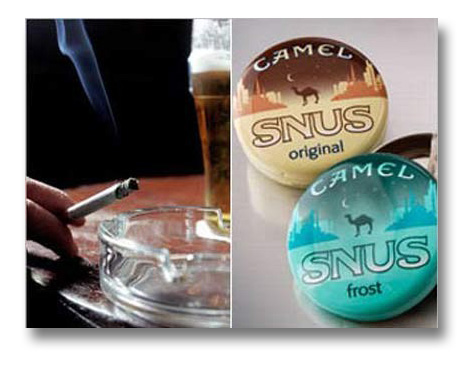

This summer Philip Morris will introduce a tobacco product called snus (pronounced, snoose) in the Dallas/Fort Worth area to test market its appeal to adult smokers. And some tobacco experts are applauding this effort.

Snus is a form of tobacco developed in Sweden that seems to be less risky than American smokeless tobacco products such as moist snuff (like Skoal), chewing tobacco (like Red Man) or dried, powdered snuff (Dental, Tube Rose, Peach and other brands).

Using snus for smoking cessation falls under the banner of “harm reduction,” and has some support in the field of tobacco control. Such an approach seems appealing: By reducing a smoker’s dependence on cigarettes, switching to smokeless tobacco (particularly snus) potentially reduces the risk for a whole host of smoking-related illnesses.

Harm reduction has been used successfully in other addictions: methadone administration for heroin addicts, for example, or clean needle exchanges for injecting drug users.

But residual tobacco-related health risks remain when a smoker quits by using smokeless tobacco, and these risks are not trivial when compared to quitting totally.

Less Risk Is Still Risk

Although smokeless tobacco is much less risky than cigarettes, nonetheless mouth cancer and poor oral health definitely occur. There are also studies among large populations that show cardiovascular disease and even death by using this product.

Overall, in terms of cancer, the risk of developing mouth cancer drops from an eight-fold increased risk to a 1.2-fold increase risk when switching from cigarettes to smokeless tobacco. This is an impressive drop, but still leaves a 20 percent increase in mouth cancer risk compared to the use of no tobacco at all.

Smokeless tobacco use also seems to be associated with increased blood pressure. Among 135 middle-aged healthy volunteers, smokeless tobacco users had on average a five-point elevation in blood pressure measured throughout the day.

Another large study among over 30,000 construction workers showed that smokeless tobacco users were nearly two times more likely to have higher blood pressures than nontobacco users. This study was not without limitations, but is plausible in the light of other evidence.

Other studies, while not definitive, indicate that smokeless tobacco users may have higher rates of diabetes and abnormal cholesterol levels.

Furthermore, among youth, use of smokeless tobacco correlates with other risky behaviors such as alcohol and marijuana use, higher rates of carrying weapons, increased physical fighting, and sexual activity without condom use.

Nonetheless, some leading tobacco control advocates have championed smokeless tobacco as a means of kicking the smoking habit.

To an extent, they do have a point: Stopping smoking, even by switching to smokeless tobacco, would greatly reduce the burden of tobacco-related illnesses in the United States. They also argue that many smokers have already made the switch to smokeless tobacco and remain smoke-free — particularly men.

But there are several reasons why, in the opinion of other well-known tobacco researchers, this approach is flawed.

First of all, the smoking cessation drugs currently on the market such as nicotine gum, patches, Zyban or Chantix are very safe and carry no cancer risks.

Most devastatingly, however, there are no randomized, double-blinded placebo controlled clinical trials that compare the success of quitting smoking by using smokeless tobacco versus using a placebo.

The name of this type of study design is a mouthful, but basically boils down to a totally unbiased study. Such clinical trials are the gold standard in terms of determining if a given treatment actually works.

There is only one small, “un-blinded” study without placebos or control subjects that advocates point to as evidence that smokeless tobacco works as a smoking cessation aid. Such a study design would not be accepted by any scientific association as even mediocre evidence to support the use of snus as a means of smoking cessation.

Many of the other studies that these researchers cite are surveys of people who had never used tobacco. While these studies may suggest an association between snus use and smoking cessation, in the scientific community a survey like this is a very poor method for determining a treatment’s success.

Furthermore, virtually all of the harm reduction studies predate the introduction of the extremely safe and exciting new drug Chantix (varenicline), which shows the most promise of any smoking cessation drug on the market.

Nor do the harm reduction experts acknowledge that combination therapy — using the nicotine gum or patch (or both) combined with, say, Zyban (bupropion) — can be quite powerful and safe.

None of these pharmaceutical approaches has cancer-causing potential; smokeless tobacco on the other hand increases the risk for cancer by at least 20 percent, and also is associated with poor oral health.

A Dangerous Alternative

It is in this context that cigarette maker Philip Morris has announced its new campaign to introduce snus. Starting in August, this company will test market Marlboro Snus in the Dallas/Fort Worth area.

According to Philip Morris’ Web site, “Marlboro Snus is a smokeless tobacco pouch product designed especially for adult smokers in the U.S.”

With harm reduction in mind, Philip Morris states, “We are introducing this product into the Dallas/Fort Worth area to understand adult smoker acceptance.”

Of course, even Philip Morris on its Web site admits the obvious: smokeless tobacco carries risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease and other oral diseases, can cause adverse birth outcomes among pregnant women, and is not a safe alternative to smoking.

They also acknowledge that the U.S. surgeon general has determined that smokeless tobacco use is addictive.

Taken together, all of the evidence points toward this unambiguous public health message: Tobacco use in any form must stop.

With new, safe and effective smoking cessation aids on the market — and more being currently studied — it seems unethical to promote smokeless tobacco as a means to quit smoking. Even in the name of harm reduction.

Dr. John Spangler is director of tobacco-intervention programs and a professor of family medicine at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.