January 27, 2016

By Dr. Rachel Tompa / Fred Hutch News Science

U.S. cancer centers unanimously call for increase in vaccine use for cancer prevention.

Amid recent talk of “moonshot” cancer cures and new treatments in development, it can be easy to forget that we already have an effective, simple way to prevent at least six types of cancer.

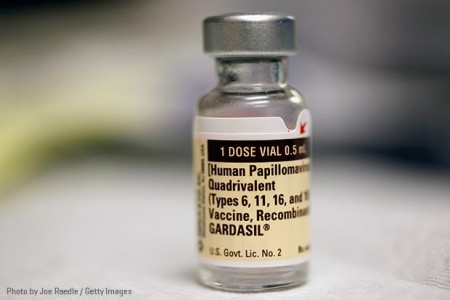

It’s called the HPV vaccine and it protects people from infection with the strains of human papillomavirus responsible for causing nearly all cervical and anal cancers, as well as many other genital cancers and certain head and neck cancers. And it’s not getting used.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all adolescent boys and girls receive the three-dose vaccine series at age 11 or 12. But in 2014, only about 40 percent of eligible teenage girls and just over 21 percent of boys had received the full course, according to the CDC’s latest data.

Now, all 69 National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers are joining together to voice their frustration at the low uptake of the HPV vaccine — with the hope of refocusing the lens of the vaccination discussion on cancer prevention.

Public debate about the vaccine — and, possibly, the low levels of vaccine use among adolescents — likely stems from the virus’ sexual transmission, said Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center virologist Dr. Denise Galloway. Galloway made critical discoveries linking HPV to cervical and other cancers and her laboratory helped lay the groundwork that made the vaccine’s development possible.

“[The low uptake] has to do with it being considered a vaccine to protect against a sexually transmitted infection, that’s likely the case,” said Galloway in a previous interview. “Even though hepatitis B should fall in that same category, it’s been portrayed more as protecting against a liver disease.”

Galloway and her colleagues at Fred Hutch, which is among the NCI-designated cancer centers issuing the statement in support of HPV vaccination, want parents and adolescents to think about the HPV vaccine in the light of cancer, not sex.

“I think people in the United States are leery of vaccines or they don’t trust pharma or they don’t want to talk about sex,” Galloway said. “So something that could prevent cancer is not having the impact that it should.”

Proactive steps to combat a public health threat

Even though so few U.S. families are following recommendations for this particular vaccine, it is still having a positive effect: HPV infection rates among adolescent girls dropped from nearly 12 percent in the years before the vaccine was routinely available to about 5 percent after the vaccine was introduced in 2006.

The CDC also estimates that every year, 27,000 men and women are diagnosed with HPV-driven cancers. The majority of these diseases can be prevented with currently available HPV vaccines.

“The HPV vaccine is an amazing public health advance, but it doesn’t guarantee eradication of HPV. It’s important to remember that the vaccine works best in those who haven’t been infected with the virus, which means, essentially, people who are not yet sexually active,” said Dr. Gary Gilliland, president and director of Fred Hutch.

The cancer centers’ consensus statement arose from a summit held at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston last November to discuss concerns about low HPV vaccination rates in the U.S. and ways to improve uptake. Experts from more than half of NCI-designated cancer centers, the NCI, CDC and American Cancer Society met at the event, starting conversations to develop the shared endorsement for HPV vaccination.

The statement also echoes the spirit of President Barack Obama’s recent call for a “moonshot” to cure cancer. In 2013, the President’s Cancer Panel, comprised of expert advisers to the president on cancer-related topics, chose to focus its yearly report and recommendations on improving HPV vaccine uptake.

“The President’s Cancer Panel applauds the NCI-designated cancer centers for issuing this consensus statement urging HPV vaccination for the prevention of cancer in support of the Panel’s recommendations,” Dr. Barbara Rimer, chair of the panel, said in an email. “We are confident that if HPV vaccination for girls and boys is made a public health priority, hundreds of thousands will be protected from these HPV-associated diseases and cancers over their lifetimes.”

Cancer center representatives hope that by joining together, they will send a stronger message to the U.S. public that the vaccine is a safe and important means to prevent potentially deadly cancers.

“Every day we delay, that means more people are going to get infections that in the future could end up causing cancers that could have been prevented,” said Dr. Melinda Wharton, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, at the summit. “There really is great urgency to stop this from happening.”

Addressing concerns

Many parents have real concerns that may put up barriers to agreeing to the vaccine, Galloway said. These barriers range from worries about the vaccine’s possible side effects to fear that vaccinating against an STD could increase teen sex to a lack of awareness of the benefits of the vaccine.

Many care providers aren’t following the CDC’s guidelines to improve HPV vaccine uptake among their patients. A 2015 survey led by researchers at Harvard Medical School found that more than a quarter of physicians don’t strongly endorse the vaccine or bring it up to families at the recommended time. And nearly 60 percent said they recommend the vaccine more strongly to adolescents they felt are at high risk of HPV infection, even though public health officials say everyone should receive the vaccine to increase herd immunity.

“There’s some reluctance and ambivalence among a lot of primary care providers in terms of just building HPV vaccination into the normal course of care,” said the NCI’s Dr. Robert Croyle at the MD Anderson summit.

Here’s a quick roundup of expert responses to some of the most common barriers to HPV vaccination:

Does it work? The HPV vaccine works incredibly well to protect against several strains of HPV. Although it’s too soon to say whether the vaccine is going to reduce rates of HPV-related cancers on a population level, there have been studies done on reduction of precancerous lesions and genital warts, which are earlier indications that the vaccine is working to reduce HPV in the population. “If you look at places like Australia or parts of the U.K. where the uptake of the vaccine is 80 percent, and you look at the earliest manifestation of HPV-associated disease, which is genital warts, there’s virtually none in Australia. And not only was there none in the girls, who they started vaccinating in 2006, but there’s none in boys, who weren’t vaccinated until 2012. Herd immunity really works if you can get high uptake of the vaccine,” Galloway said.

Will it increase teen sex? No — a large 2015 study found that girls aged 12 to 18 who’d received the HPV vaccine did not have increased sexual activity as compared to teens who hadn’t been vaccinated.

Is it affordable? Yes — The Affordable Care Act mandates coverage of the vaccine by private insurance plans. In Washington state, the HPV vaccine — like all childhood vaccines — is free to children aged 18 and under. Nationwide, the CDC provides free vaccines for children who can’t afford to pay for them through the Vaccines For Children program.

Is it safe?Yes — like every other CDC-recommended vaccine, the three HPV vaccines on the market have been through rigorous safety testing before their release to the public. Since the vaccines’ release, there have been numerous studies in the U.S. and Europe of hundreds of thousands of adolescents who received the vaccine — and again, no adverse safety effects have been found to be linked to the vaccine.

*This news story was resourced by the Oral Cancer Foundation, and vetted for appropriateness and accuracy.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.