Source: www.dentistryiq.com

Author: Dennis M. Abbott, DDS

The face of oral cancer has changed: No longer is oral cancer a disease isolated to men over 60 years of age with a long history of smoking and alcohol consumption. Today, the demographic for the disease includes younger people of both sexes with no history of deleterious social habits who are otherwise healthy and active. It spans all socioeconomic, racial, religious, and societal lines. In other words, oral and oropharyngeal cancer is an equal opportunity killer. Today, as you read this article, 24 people in the US will lose their battles with oral cancer. That is one person for each hour of the day, every day of the year. Each of those lost is someone’s sister, a father’s son, a small child’s mommy, or maybe even a person you hold dear to your heart. The truth is, oral and oropharyngeal cancer has several faces . . . and each of those faces is a human being, just like you and me. So how can we, as dental professionals, be instrumental in the war against oral and head and neck cancer?

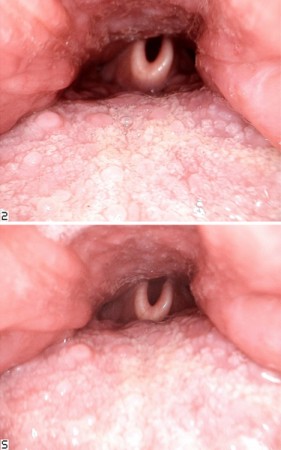

Views of the oropharynx, the base of the tongue, and the epiglottis, taken with the Iris HD USB 3.0 intraoral camera using different points of focus.

Photos courtesy of the author.

The answer, as with most other cancers, lies in early detection. When oral and oropharyngeal cancer is detected early, the five-year survival rate can be as high as 80% to 90%. The harsh reality is that most oral and head and neck cancers are only found at late stages after the cancer has advanced—often to the lymph system. As a result, the chance of the person living for five years after diagnosis falls to approximately 55%.

As dentists and dental hygienists, we—like it or not—are on the front line of this war. We often have the opportunity to see potential cancer patients more frequently than our medical colleagues do, and we are trained to see abnormalities inside the mouth and in the head and neck region. (This is a huge part of the solution!) Many of my medical colleagues tell me that they do not have the training to see what I can see in the mouth. But I do not have the training to practice oncological medicine like they do. The truth is, it takes all of us doing our jobs to care and manage the individual person—not just the teeth, not just the liver, not just the breast, but the whole patient.

Years ago, we could almost profile who would or would not be likely to present with oral cancer. It was always the “Marlboro man”—that guy who was older, drank alcohol frequently, and had a smoking pack-year history that was two or three times his age. But those days are long gone. With the recent understanding that the human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, is an etiological factor for oral and oropharyngeal cancer, virtually everyone is a potential cancer patient. As such, everyone should be screened. While the individual with classic risk factors still remains at risk for developing oral cancer, many who present with HPV-related oral and head and neck cancers have no other discovered risk factors, other than exposure to HPV and an immune system that, for reasons still unknown, will not adequately clear the virus without repercussions.

It is believed that 80% to 90% of all Americans have been exposed to HPV at least once in their lifetimes. Most people manage to clear the virus through the immune system’s normal defense function within six to seven months; in some patients, however, damage takes place at the cellular level that may take months, years, or even decades to manifest as cancer. The majority of HPV-related oral and head and neck cancers present in areas that are difficult for us as dental professionals to visualize, such as the tonsils, the base of the tongue, the oropharynx, the posterior pharyngeal wall, and the larynx. That, however, does not give us an excuse not to screen in these areas . . . we just have to think outside of the box and get creative about how we screen.

Visual inspection combined with palpation remains the essential foundation of screening for oral and oropharyngeal cancers, but where visualization is difficult—such as with the base of the tongue and the lower oropharynx—knowing and asking the right questions can become critically important for identifying potential concerns:

“Are you noticing any unusual hoarseness?”

“Are you having any difficulty swallowing?”

“Do you ever have a sensation as though something is caught in your throat?”

“How long has that tonsil been inflamed?”

“Have you noticed any sinus or allergy issues since that tonsil has been enlarged?”

While these questions may seem unrelated to teeth, they are not unrelated to oral health. Simply asking the right questions can open a dialogue of discovery that may lead to the detection of an oropharyngeal cancer early. And early detection is the key to beating the disease and maintaining a good quality of life during the survivorship years.

Technology-based adjunctive devices to assist the dental professional in the early detection of oral cancer have existed in the market for the past 10 to 15 years. Much has been written about fluorescence and reflective technologies, which help the examiner to detect subtle changes in tissue through the usage of light in the violet and yellow ranges of visible light, respectively. Examination with these wavelength-specific devices enhances visualization by highlighting changes in the oral mucosa and vasculature. Usage of these adjuncts has also demonstrated value in enabling clinicians to better understand the size of affected tissue surrounding suspected lesions. As such, these may be useful in selecting a field for biopsy that may produce clear, or noncancerous, margins.

Since the completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP) in 2003, there exists a more clearly defined understanding of how diseases such as cancer affect our cells at the nucleic acid level and how genetic mutations can serve as risk factors or catalysts for cancerous changes in cells. Technology used in the HGP has also provided insight into the genotyping of viruses, leading to a sharper picture of how viral interaction with our genetic code can lead to disease. Today, the dentist and dental hygienist have this technology readily available to move their practice into the era of personalized health.

Salivary tests, such as the MOP (Molecular Oral Testing) by PCG Molecular, take advantage of innovative, advanced genetic testing to establish the risk or presence of oral or oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. MOP does this by evaluating cellular abnormalities in the oral cavity and oropharynx, DNA damage associated with oral and oropharyngeal cancer, and the presence of HPV. With this information, the clinician can better determine the appropriate course of action for the patient.

Sometimes striving to provide the best possible patient care means thinking outside of the box to use technology designed for one purpose and discovering a new application to meet an unanswered need. Most of us are at least familiar with intraoral cameras, and many of us have them in our offices. Using the magnified imagery of a quality intraoral camera and a high-resolution monitor, this tool is a favorite device for illustrating the need for proposed treatment and for establishing patient trust. But what if we could use those images to possibly save a life?

The Iris HD USB 3.0 intraoral camera by Digital Doc LLC has catapulted intraoral photography into the high-definition age. Using the Iris HD precision optical lens array and an advanced HD sensor from Sony, the Iris HD USB 3.0 provides unmatched 720p-resolution clarity that is perfect for the magnification and photographic capture of suspicious areas discovered during a thorough head and neck examination/oral cancer screening. Because of the size of the camera head, the device even makes it possible to examine areas of the oropharynx that were previously difficult for dentists and hygienists to visualize.

Of course, the camera cannot substitute for laryngeal endoscopy, especially if cancer inferior to the epiglottis is suspected, but the camera’s ability to see beyond the palatopharyngeal arch is an improvement over an angled dental mirror. Most patients can tolerate the necessary posterior placement of the camera to capture an oropharyngeal image either by breathing through the nose or with placement of a topical anesthetic on the posterior soft palate and uvula to suppress the gag reflex.

Regardless of the power of the technology, the ultimate skill in detecting early-stage oral and oropharyngeal cancer lies in the eyes, hands, and brain of the examiner. Careful inspection, knowledge, discernment, and experience are the real tools of the professional for acquiring and processing all of the available data and for correctly fitting the puzzle pieces into a picture that illustrates either health, concern with reason for reevaluation, or the need to biopsy the area in question. When reevaluation is required, no more than two weeks should elapse between the initial examination and follow-up, as time is of the essence in proceeding to treatment should the suspicious area indeed be cancerous.

Responsibility to the patient does not end with an abnormal screening result. The dental professional should have a plan in place to either biopsy or refer. The dental professional should biopsy only if he or she is well-experienced in the removal of suspected cancerous lesions. Otherwise, the patient should be referred to an oral/maxillofacial surgeon, periodontist, otolaryngologist, or head and neck surgeon who is comfortable with and experienced in the safe and effective biopsy of a potentially cancerous area. It is most often the case that only one opportunity to obtain a diagnostic tissue sample exists, so the skills of the doctor performing the biopsy should be without question. Every effort should be made to ensure that the patient is seen promptly for biopsy and that the pathology results are returned and shared with the patient expeditiously. Delay can be detrimental to the survival of a patient with oral or oropharyngeal cancer.

Should a screening result from your office lead to a diagnosis of oral or oropharyngeal cancer, be prepared to counsel and educate your patient about what to expect in his or her cancer journey. Learn about and be prepared to meet the unique dental and oral health needs of patients with oral and head and neck cancers, and become equipped to continue care for your patients throughout their treatment and into survivorship. For all of the destruction and hardship that cancer brings, it can form unbreakable bonds, between doctor and patient and between dentist and physician.

Don’t be afraid to reach out to your counterparts in the medical community and bridge the gap between medicine and dentistry in your area. Form alliances with head and neck surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and oncology nurses. Let them know about your skills and the services and technology available in your office that place you on the front line of this war on oral cancer. Take time to understand your medical colleagues’ role in treating the disease and become familiar with the technology they are using to save lives and diminish the long-term effects of oral cancer treatment. We are, after all, fighting the same war, and we’re all on the same side. It is all of us against oral and oropharyngeal cancer, with the needs and health of that one patient we’re fighting for leading us in the battle.

About the author:

Dennis M. Abbott, DDS, is the founder and CEO of Dental Oncology Professionals, an oral medicine-based practice dedicated to meeting the unique dental and oral health needs of patients battling cancer. In addition to private practice, he is a member of the dental oncology medical staff at Charles A. Sammons Cancer Center at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas. Dr. Abbott is also the founder of the American Academy of Dental Oncology and serves as a consultant to the national American Cancer Society in the development of oral monitoring guidelines for post-treatment cancer survivors. Dr. Abbott lectures internationally on the topics of dental oncology and oral cancer.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.