Source: cen.acs.org

Author: Erika Gebel

Medical Diagnostics: A simple and inexpensive device detects multiple cancer biomarkers

When doctors spot cancerous lesions in patients’ mouths, it’s often too late: The disease has already reached a difficult-to-treat stage. As a result, oral cancer has a high death rate. To help doctors catch the disease earlier, researchers have developed a simple, low-cost method to identify multiple oral cancer biomarkers at once (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac301392g).

Scientists previously have shown that oral cancer patients have altered levels of several proteins, including vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C), in their blood (J. Clin. Pathol., DOI: 10.1136/jcp.2007.047662). Doctors would like to use these biomarkers to diagnose the disease.

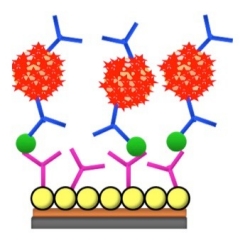

A magnetic microbead (beige) covered in horseradish peroxidase (red stars) and antibodies (blue) captures an oral cancer protein (green circle). Another antibody (pink), which is attached to gold nanoparticles (yellow) on the surface of an electrical sensor, binds to the same cancer protein. When researchers add peroxide to the mix, the peroxidases generate an electrical signal proportional to the cancer protein’s concentration. Credit: Anal. Chem.

But James Rusling of the University of Connecticut, Storrs, says that to improve diagnostic accuracy, it’s necessary to detect multiple proteins at once. What’s more, current technology can’t easily measure subtle changes in the low concentrations of these proteins found in patients’ blood. Such tests would require trained technicians and expensive equipment, such as spectrometers, that most clinics don’t have. Rusling and his colleagues, including J. Silvio Gutkind of the National Institutes of Health, wanted to develop a low-cost test doctors could easily use.

The team built a device that can measure concentrations of multiple biomarker proteins at once through easy-to-read electrical signals. For each protein they want to detect, the scientists use two antibodies that each bind to a different part of the biomarker. One antibody decorates magnetic microbeads. The team also coats these microbeads with a thick forest of some 400,000 copies of the horseradish peroxidase protein, an enzyme that reacts with hydrogen peroxide to produce a current.

In a blood sample, the microbeads capture the specific oral cancer protein. Then the researchers apply the microbeads to a disposable chip with electrical sensors. On the surface of the sensors are gold nanoparticles that the researchers had covered in the second antibody. Antibodies on the gold nanoparticles grab onto the beads via the captured biomarker. The scientists repeat this process for each biomarker they want to measure. Their device contains a chip with room for eight sensors.

The nanoparticles on the chip conduct the electron flow produced by the peroxidases through the chip’s circuits. The resulting electrical signal is proportional to that biomarker’s concentration. In initial tests of the device, the researchers found that the concentrations of the biomarkers measured using this method matched those made using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, the gold standard for protein detection.

To test the method’s diagnostic capabilities, the researchers measured levels of four oral cancer biomarkers: interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8, VEGF, and VEGF-C. For each biomarker, they mixed the corresponding magnetic microbeads with diluted serum samples from 78 oral cancer patients and 49 cancer-free people. Using a small magnet, they pulled out the beads from the serum. After injecting the beads into a microfluidic chamber atop the sensor chip, they added a hydrogen peroxide solution to the chamber and measured the resulting electrical signal.

They found a detection limit for the device between 5 and 50 fg of protein, depending on the biomarker. Based on this small data set, the researchers estimate that their method could correctly diagnose oral cancer in 89% of people with the disease and rule it out in 98% of healthy people.

“They demonstrated a very impressive detection limit,” says Chang Lu of Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University. He thinks the technology is practical for hospital settings, and he hopes Rusling will extend it to diagnose other types of cancer. Rusling is already adapting the method to diagnose prostate cancer.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.