Source: www.cancer.gov/ncicancerbulletin

Author: Eleanor Mayfield

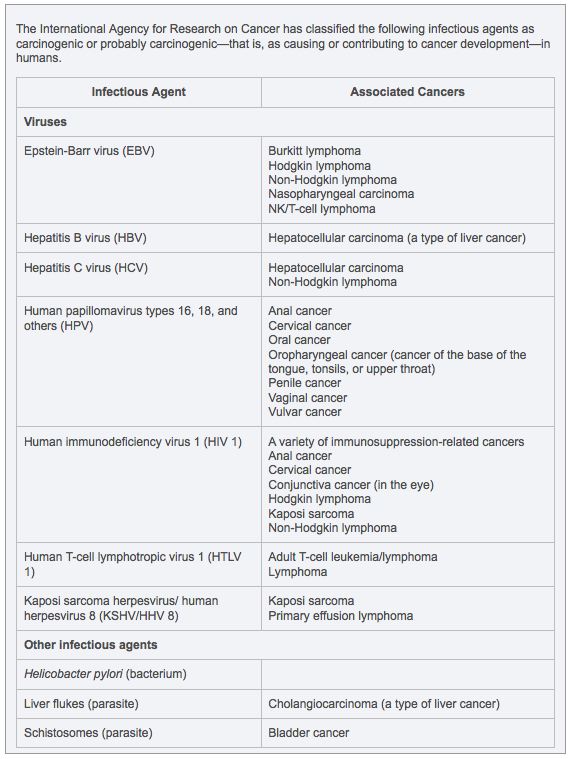

Few people associate infection with cancer, but close to one-fifth of all cancers in the world are caused by infectious agents, including viruses, bacteria, and other microbes. In developing countries, the number is higher—about one in four—while in industrialized countries, such as the United States, it is about one in 12.

Infectious agents that can cause cancer are extremely common, infecting millions of people around the world. Yet it is rare and takes a long time for an infection to develop into cancer. “You need a lot of things to happen, or not happen, to get from an infection to cancer,” said Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, chief of NCI’s Laboratory of Cellular Oncology and a leader in the molecular biology of tumor viruses.

The microbes responsible for most of the global burden of infection-associated cancer are: the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which causes gastric cancer; cancer-causing strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV), which cause cervical cancer and other cancers; and the hepatitis B and C viruses, which cause liver cancer. These four microbes alone cause more than 15 percent of all cancers worldwide.

Other cancers known to be associated with infectious agents include leukemia and lymphoma; anal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancer; and tongue and throat cancers. Last week, researchers reported new evidence linking aggressive prostate tumors to a virus.

Role of the Immune System

Microbes can lead to cancer by a variety of mechanisms that are not yet fully understood, explained Dr. Allan Hildesheim, chief of NCI’s Infections and Immunoepidemiology Branch. The cancer-causing strains of HPV are known to disrupt the cell cycle and inactivate tumor suppressor proteins such as p53, which enables genetic damage to accumulate and, eventually, a cancer to form, he explained. H. pylori is believed to induce chronic inflammation, which can lead to atrophic gastritis and, over time, increases the risk of developing gastric cancer.

“In the case of the hepatitis B and C viruses, the problem may be less the infection itself than the immune system’s response to it. To fight off the infection, the immune system releases cytokines and other inflammatory proteins that can cause tissue damage,” said Dr. Hildesheim. “Over time this can lead to cirrhosis of the liver, which is a strong predisposing factor for liver cancer.”

Chronic suppression of the immune system is another cause of infection-associated cancer. People infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which weakens the immune system, and organ-transplant recipients who take immunosuppressive medications to prevent transplant rejection are more vulnerable to infection-associated cancers than people whose immune systems function normally.

Similar Molecular Process

The molecular chain of events leading to an infection-induced cancer is similar to the process by which noninfectious cancers develop, said Dr. Patrick Moore, who directs the Molecular Virology Program at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute. “The same tumor-suppressor signaling pathways that are mutated in noninfectious cancers are also inactivated by viruses,” said Dr. Moore. “Indeed, it was through research on viral causes of cancer that we learned much of what we now know about cancer-causing genes and tumor-suppressor signaling pathways.”

The two most recently discovered viruses believed to be associated with human cancer were both identified in Dr. Moore’s laboratory. In 1993, a group led by Dr. Moore and his wife Dr generic viagra from india. Yuan Chang discovered the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, also called human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8), which is the likely cause of Kaposi sarcoma. In 2008, the same team found compelling evidence that a newly discovered virus dubbed the Merkel cell polyomavirus causes most cases of Merkel cell carcinoma, an uncommon but lethal skin cancer.

Opportunities for Intervention

Cancers caused by infection “offer unique opportunities for intervention,” said Dr. Lowy. “We now have two vaccines—against hepatitis B and HPV—that can prevent cancer by preventing infection with the virus. Secondly, at least in theory, you can take aim at genes or proteins made by the infectious agent. The best example to date of this approach is antiretroviral therapy for HIV, which works because it has a much stronger effect on the genes and proteins made by the virus than on the body’s own genes and proteins.”

Many features of infection-associated cancers remain poorly understood. For example, for most of these cancers, only some cases are caused by infection. “Some liver cancers have nothing to do with hepatitis infection,” said Dr. Lowy. “Some oropharyngeal, vulvar, and penile cancers are caused by HPV infection, but others are not. On the other hand, virtually all cases of cervical cancer seem to be caused by HPV.”

Burkitt lymphoma in Africa is almost always caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), added Dr. Moore, whereas in the United States fewer than half the cases of this disease have a viral cause. “What we previously thought was a single cancer has been shown to be two or more types of cancer that look similar, some caused by a virus and some not.”

Some microbes, including EBV, cause different types of cancer in different parts of the world. “In southern China, nasopharyngeal cancer [a cancer of the throat] is the most common cancer manifestation of EBV infection,” said Dr. Hildesheim. “In sub-Saharan Africa, you rarely see nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but Burkitt lymphoma is relatively common.”

Genetic Susceptibility

The fact that most infections capable of causing cancer are very common, and yet only a small subset of those infected develop cancer, suggests that genetic and other factors may promote or protect against cancer in infected individuals, continued Dr. Hildesheim. “Those of us who study tumors caused by infectious agents have been a bit late joining the genetic revolution,” he said. “There is a tremendous amount we can learn.”

Recently he and his colleagues reported on the link between cervical cancer and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—one-letter changes in the human genetic code—in genes involved in the immune response to infections and in the repair of DNA damage. They noted that some genetic polymorphisms are associated with increased risk of persistent HPV infection, a prerequisite for an HPV-induced cancer, while others are associated with the tendency for HPV-infected cells to progress to precancer or cervical cancer. Parallel studies have also confirmed findings by other researchers that certain variations in immune regulation genes known as HLA genes appear to affect cervical cancer risk.

“We are trying to understand how individual genetic factors may interact with HPV infection to predispose, or protect against, persistence of the infection or alter the ability to repair genetic damage caused by persistent HPV infection,” Dr. Hildesheim explained. “We and others are also studying whether differences in the genetics of HPV might explain why some infected individuals develop cancer while others do not and whether differences in the genetics of EBV may help to explain why the pattern of cancers associated with this virus is so different in different parts of the world.”

By better understanding cancer-causing infections, said Dr. Lowy, “the hope is that we will be able to prevent more cancers by preventing the infections that lead to the disease or by treating the infections before they develop into cancer.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.