Source: http://med.stanford.edu

Author: Tracie White

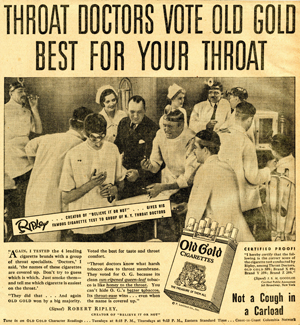

Tobacco companies conducted a carefully crafted, decades-long campaign to manipulate throat doctors into helping to calm concerns among an increasingly worried public that smoking might be bad for their health, according to a new study by researchers at the School of Medicine. Beginning in the 1920s, this campaign continued for over half of a century.

“Tobacco companies sought to exploit the faith the public had in the medical profession as a means of reassuring their customers that smoking was safe,” said Robert Jackler, MD, the Edward C. and Amy H. Sewall Professor in Otolaryngology.

“Tobacco companies dreamed up slogans such as, ‘Not one single case of throat irritation with Camels;’ then, to justify their advertising claims, marketing departments sought out pliant doctors to conduct well-compensated, pseudoscientific ‘research,’ which invariably found the sponsoring company’s cigarettes to be safe,” Jackler said. “The companies successfully influenced these physicians not only to promote the notion that smoking was healthful, but actually to recommend it as a treatment for throat irritation.”

Jackler is the senior author of the study, which was published in the January issue of The Laryngoscope. Hussein Samji, MD, a recent Stanford residency graduate, was his co-author.

Using internal documents from tobacco companies from the Legacy Tobacco Document archives, the study’s authors reviewed a wealth of correspondence, contracts, marketing plans and payment receipts that shed light on the industry’s multifaceted, highly effective campaign.

Jackler’s ongoing research into the history of tobacco company advertising has resulted in several published studies on the topic, sparked in part by his collection of thousands of historical cigarette ads exhibited online at http://tobacco.stanford.edu, the originals now donated to the Smithsonian Institution. He also spearheaded a group called the Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, which analyzes the effects of tobacco advertising, marketing and promotion.

In the new paper, the authors describe how tobacco companies regularly hosted “hospitality booths” at otolaryngology conventions from which they gave out free cigarettes, sometimes with packs embossed with the doctors’ names. In major cities all over America, throat specialists were taken out to elegant dinners at which they were implored to “prescribe” their brand of cigarettes to patients with sore throats or coughs.

When the government, through the Federal Trade Commission, tried to intervene against “hucksterish” advertising slogans promoting the healthfulness of their cigarettes, prominent otolaryngologists were recruited to defend the validity of the blatantly false claims.

“The list of recruitments who served as experts testifying on behalf of tobacco interests includes a virtual who’s who of leading otolaryngologists in the 20th century, including many leading head and neck cancer surgeons,” Jackler said.

Even after the Surgeon General’s Report of 1964 definitively linked smoking with cancer of the voice box (larynx), the otolaryngology departmental chairs of four major universities testified before Congress in opposition to the findings.

“It was especially disappointing to discover that leading otolaryngologists took public positions exculpating tobacco even after the definitive Surgeon General’s report,” the study said.

The authors emphasized the importance of collaboration between doctors and industry for continued advances in medicine, but pointed to this study as a reminder to the medical community of the need to adhere to the “highest standards of scientific validity” and to remain vigilant in the advocacy for patients’ interests when working with industry.

“Ethically, a physician must always act on behalf of the well-being of patients,” Jackler said. “Responsible industries balance their need to maximize profits with a commitment to improve the health of their consumers.”

Note:

1. This research was conducted as part of the Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. The school’s Department of Otolaryngology also supported the research.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.