- 5/11/2004

- Dave Kindred

- Golf Digest

Hubert Green said, “That pine tree, the tall one, all the way to the left.” He looked at the tree through a range finder. “It’s 144, 145 yards.”

It was one of those bright winter days in Florida when the sun is betrayed by a chilling wind off the Gulf of Mexico. The breeze came past that pine tree, came against Green’s face. Because he’s diabetic, his hands and feet quickly get cold. He was uncomfortable. He wore shimmering blue slacks, a blue sweater over a blue long-sleeved shirt, and the wide-brimmed leather hat that is his trademark. He’d driven his golf cart onto the back practice tee at Hombre Golf Club, his home course in Panama City Beach. In a red plastic crate, he’d brought along a couple hundred Callaway reds, each ball marked with an inked circle and inside the circle the initials “HG.”

He hit five, six balls with a 9-iron. Earlier, he’d said he felt weak. Instead of the club hitting the ball, it was like the ball hit the club. A 9-iron might go 110 yards, a measure of strength so dispiriting that he said, “Right now I couldn’t play on the LPGA Tour.” On the practice tee, he moved to a 5-iron. A little draw, pretty enough. Nine, 10 swings. The balls fell 10, 15 yards short of that left pine tree.

He turned and said to the only other player on the range, “Whatcha hitting?” “Five-iron,” said Allen Doyle, another Champions Tour star, and Green rolled him a ball, asking him to hit it at that last pine tree, the one 144, 145 yards away. Doyle’s 5-iron flew over the pine. Green watched, said nothing.

Someone remarked on the wind coming at the players. These next words Green said through tight lips: “Freakin’ hurricane. I can hit a 5-iron 145 yards.”

What we know to be true is not always what we want to know. Hubert Green knows it to be true that so soon after his cancer he cannot be the Hubert Green who was one of the great players of his generation.

He knows it. Says it out loud. Still, he wants it. He’s a hard case, little different at age 57 than 27, ornery, funny, proud. Green’s longtime friend and contemporary, Billy Kratzert, says, “Hubert just expects so much of himself, and he goes at everything head-on. Only problem is, he wants it yesterday. He’s the king of wanting it yesterday.”

Now, on the range, he wants it to be yesterday. He wants to be able to scream a 5-iron 185 yards into the freakin’ teeth of a hurricane.

But it’s not happening. “Got nothing from here,” he said, bringing the 5-iron halfway down, “to here,” moving it to impact. He hit maybe 25 balls, then packed up his stuff. “Not very impressive, eh?”

Four months earlier, Hubert Green was all but dead. Any dead man in August who draws 5-irons into a December breeze is impressive.

It began at his dentist’s. At a regular cleaning in April, Dr. Stephen Myers saw a swollen, abnormal area on the back left of Green’s tongue. On May 26, doctors told Green he had cancer. He remembers nothing else of what the doctors said, nothing that made sense. He heard words, words all around him, pieces of ice on the air, floating, brittle. At the back of his neck, there by the hairline, fear arrived. Doctors said the cancer was at Stage 4, the killing stage. It was on the back of his tongue and a tonsil. They talked about treatments. None of the information made it through the fear shaping itself to the man with the cancer. He knew cancer.

Green’s father was 75 when he died in 1975 of cancer that began on his stomach. The son remembered Dr. Albert Huey Green’s customs of each April at the Masters. “He’d walk down 1, down the right side on 2, and stop by a tree on that hill to watch us play out and hit tee shots on the third,” Green said. He sat at home. Sunlight danced on the gulf waters. Tears filled his eyes. “After he passed away, I found myself turning on 2 and looking back. He wasn’t there.”

Treatment for Green’s cancer wouldn’t start until July 2. So he did what he has always done. Played golf. “What else am I going to do, feel sorry for myself, ‘Oh, woe is me’? I’d have gone crazy sitting at home.”

A Billy Kratzert story: “The week after he found out he had cancer, Hubert’s playing a skins game before the Senior PGA with me, Fuzzy Zoeller and John Calabria. Hubert, of course, is in every fairway. And on the first four holes I’m in rough you can’t get out of. Well, he is all over me. So I say, ‘Hubert, why’re you riding me so hard?’

“He says, ‘Man, I’m dying of cancer, this might be the last time I ever get to give you a bunch of [grief].’ I say, ‘Here I am, feeling a little compassion for you, and you’re still that Doberman you always were.’ It was wonderful.” Green shot 77, 75, missed that cut. Two weeks later: 66, 67, 71 for his best finish of the season, a fourth in the Farmers Charity Classic. Then, 30th in the U.S. Senior Open where, on June 29, he played his last round of 2003. By August, done with chemotherapy and radiation, he considered playing a Champions event the next week.

He reported it himself in a way that calls for elaboration. He’d set up a website, HubertGreen.com, to keep friends and fans informed. It was priceless stuff, amazing, inspiring, an accounting of prayers and fears, laughs and tears, alive with the essence of Hubert Green. He began:

“I speak in a Southern type language. My spell-check on this great IBM has no chance. Sometimes I might put a capital ‘S’ to emphasize sarcasm. ‘R’ will stand for Redneck-ese. (S) I will try to include some highly intelligent digs at y’all from time to time.” His wife, Michelle, becomes a lifesaving version of Nurse Ratched. His treatment is “a nine-hole match with the devil.” God is spoken of, and often, as Mr. Big, sometimes in capital letters. “The devil has no chance, thanks to y’all and MR. BIG.”

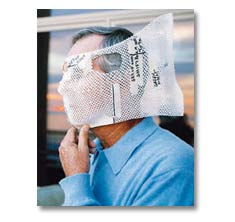

During six weeks of radiation, Green wore a white mask molded to his facial features. The idea was to hold his head still so radiation zapped only the targeted area. “If you think it’d be hard to lay still for 15, 20 minutes,” he says, “let me tell you, you can lay real still when your life depends on it.”

He sometimes carried a prop to his four-hour chemotherapy sessions: “They had these nine chairs, lined up like a barber shop, and everybody in them is dying. It’s not a happy place, everybody in pain. But I thought, ‘It’s where we are in life. Let’s lighten up.’ ”

So chemo nurse Debbie Balmer laughed when she saw Green carry in a stuffed-toy horse, Renegade, representing the mascot of his alma mater, Florida State University. “It played the Seminole fight song,” Balmer said. “Well, we’re all Gators here [at the University of Florida Health Science Center]. I went to the gift shop and bought a Gator that played our fight song louder than his. We had a fight-song war going on in chemo.” A minute of laughter, dozens of “puke days” in “Pukeville.” Green reported, “Chemo does not favor this redneck. Matter of fact, it is worse than missing a three-footer on 18 at Augusta.”

During radiation treatment, Green wore a white mask molded to his facial features to help hold his head still.

When Green missed that putt 26 years ago, three years after his father’s death, he needed it to get into a playoff with Gary Player. At the time, Green was near greatness. The previous summer he had won the U.S. Open. In 1985 he won the PGA Championship. From 1971 to 1985 he won 19 PGA Tour events. Give him that Masters and move him up from third in the 1977 British Open, he’d be with Nicklaus, Hogan, Sarazen, Player and Woods as the only six men with a career Grand Slam.

Anyway, by August, HubertGreen.com reported that its journalist might play the next week. Instead, crisis.

It was Aug. 9. At home, he suddenly felt so bad he asked his wife to take him back to the hospital. Severe dehydration, low white blood-cell count, pain. He couldn’t swallow. A feeding tube was inserted.

Then it got worse. “On the 11th,” he says, “I came close to cashing in my chips.” Disoriented, he vomited a pool of dark reddish fluid. He thought he’d seen such an eerie pool somewhere else. Three days later, he remembered where.

“My father, I was with him, vomited the same-color stuff,” Green says. “And one of the nurses came in and said, ‘Ooh.’ My mother asked, ‘What was that?’ The nurse said, ‘That’s dead man’s bile.’ “The next morning, he passed away. Thank God, when I vomited, I was on enough pain medication I couldn’t realize what I was seeing. That might have put me over the hill.”

Green went home to stay on Aug. 22, and two weeks later his journal’s headline read, “MATCH OVER — VICTORY GREEN TEAM.” He’d had another CAT scan. It showed: “The big C is no more.”

For months the basic acts of eating and talking continued to be difficult and often painful. His health remained at risk; radiation and chemotherapy destroy good cells with bad, leaving a patient with a diminished immune system. Doctors have told him that if the cancer returns, the chances are 90 percent it will do so within two years.

On that winter day when he left the practice range unimpressed, Hubert Green sat on the balcony behind the Hombre clubhouse. His weight had risen from 143 to 165, not yet his normal 180. He was tired, maybe sad, frustrated. He wanted to be golf’s Hubert Green, not cancer’s Hubert Green. And he wanted it yesterday. Talk got around to the three-footer at Augusta and the truth that being alive is a better thing than any putt. He laughed and said this next quickly, happily: “If I beat this, there’ll be more putts to make.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.