Source: newsroom.uw.edu

Author: Brian Donohue

You know how great it feels when someone makes a pie or cake just for you? University of Washington Medicine head and neck surgeons have been feeling that kind of love lately, and on Feb. 5 they shared the first slice, so to speak, with patient Steven Higley.

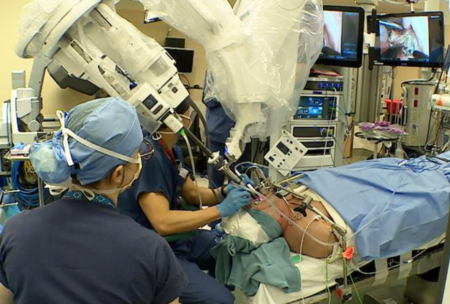

Surgical assistants work near patient Steven Higley on Feb. 5. Lead surgeon Jeff Houlton is obscured by the robotics.

The cake in this story is actually a da Vinci robotic-assist system built especially for head and neck procedures. It is easier to maneuver than the robotic device they’ve used for the past decade, which was designed for operations to the chest and abdomen.

Higley underwent surgery to have a cancerous tonsil and part of his throat removed. Sitting at a console a few feet from the patient, Dr. Jeff Houlton manipulated the miniature surgical tools emanating from the robot’s single port, positioned just outside Higley’s open mouth. It was UW Medicine’s first trans-oral surgery with the new tool.

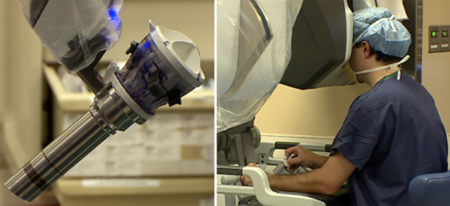

“If you think about laparoscopic surgery in the belly area, robotics provides the advantage of multiple mechanical arms approaching from different angles,” Houlton said. “But it’s a challenge to have three robotic arms that all need to go through a patient’s mouth. With this machine, the three arms are designed to come through one garden hose-like entry port and then articulate out from there.

“Pretty interesting, though, that in the past 10 years we built a nationally recognized practice for robotic head and neck surgery with a device designed for a different part of the body,” he added, laughing.

The new robot’s single port, left, through which all surgical instruments travel. At right, Dr. Jeff Houlton manipulates the instruments from a distant console. Photos by Randy Carnell, UW Medicine

Higley’s radical tonsillectomy entailed the removal of a margin of tissue beyond the visible tonsil and tumor. Houlton’s incisions exposed cranial nerves and branches of the carotid artery. Working in tight quarters with such vital anatomy, Houlton and his head-and-neck colleagues in surgery, Brittany Barber and Neal Futran, welcome the improvement in maneuverability.

Head and neck cancers represent only 3% of all oncology cases in United States. But case numbers are rising, Houlton said, with increased incidence of throat cancer involving human papillomavirus (HPV), as was the case with Higley, 68.

“Most of these cancers are HPV-mediated rather than smoking- and drinking-related,” Houlton said. “We call it an epidemic because it’s a viral cancer that’s gone up significantly since about the year 2000. In terms of HPV, cancer of the oropharynx (mouth, throat and tongue) is actually more common than cervical cancer now.”

Higley’s cancer came to light last fall after a yearly physical with his Olympia-based physician.

“I had no trouble swallowing, no pain,” Higley recalled. “I didn’t notice anything until my doctor said, ‘Hey, this looks like something we should check out.’ ” His referral to UW Medicine led to a biopsy in mid-December, and on Dec. 23, he learned that he had cancer.

“I’m glad they found it early and so is my wife,” Higley said. “If I could’ve had surgery the next day, it would’ve been OK with her.”

After the robotic part of the surgery, Houlton incised Higley’s neck and removed more than a dozen lymph nodes to be biopsied for cancer cells. Higley hopes they’ll concur with the pre-surgery PET scan that indicated his cancer was constrained to the tonsil.

Patient outcomes data suggests Higley’s prognosis is encouraging: 90-95% of patients who undergo surgery for this cancer survive five years or more.

Higley is already swallowing liquids and soft foods, but he’ll manage sore throat for about a month, Houlton said.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.