Source: www.science20.com

Authors: Emma King, University of Southampton and Christian Ottensmeier, University of Southampton

Immune cells in the blood primarily defend us against infection. But we’re now learning that these cells can also keep us free from cancer. Patients with less efficient immune systems such as organ transplant recipients or those with untreated HIV, for example, are more susceptible to cancers. It is also becoming increasingly apparent that we can use immune cells to predict survival in people who do develop cancer. And that, in fact, there are immune cells within cancers.

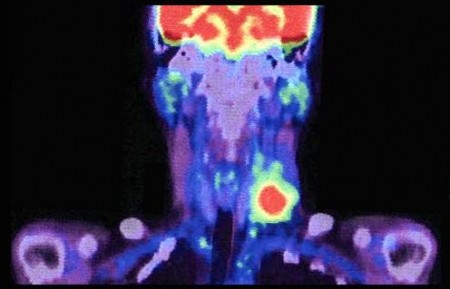

The number of immune cells inside a tumor can hugely vary: some patients have vast numbers while some have very few. In a recent study, we showed that in head and neck cancers, the survival of a patient depends on how many immune cells are within the tumor. This could be a valuable way of individualizing cancer treatments.

Patients with lots of immune cells, for example, could be offered less toxic cancer treatment while those with few immune cells may need more aggressive treatment to improve their chances of survival.

Not all immune cells within the tumor are able to “attack” the cancer. By looking at specific cell markers – proteins on the cell exterior that allow us to see whether, for example, cells are exhausted – we can determine which individual immune cells in the tumor will be effective in tackling the cancer, or if they are exhausted and not able to perform any useful function. It’s possible that these exhausted cells could be reinvigorated to become useful again with targeted immunotherapy treatments currently in development.

These include vaccines, so if a cancer has been caused by a virus, we can vaccinate the patient with a short segment of the same virus to encourage the immune system to react to it. Around 30% of head and neck cancers, for example, are the result of human papillomavirus (HPV). There has been a 225% increase in these types of cancers over the past 15-20 years and in the US, HPV will cause more of these cancers than cervical ones. In these cases, cancer cells continue to express part of the HPV on their surface. The hope is that following vaccination, immune cells will be better able to identify these HPV cancer cells and kill them.

For people who simply don’t have many immune cells in tumors, specific, targeted immunotherapy could be one option. But also broader “brush stroke” treatments. These broader treatments cover all immunotherapies that encourage a patient’s immune system in a fairly non-specific way. Our immune cells are normally very tightly regulated and include many fail-safe systems to prevent them from over-reacting primarily to infections. General immunotherapy takes the brakes off and allows the immune cells to react to the cancer cells.

It may be that a combination of specific vaccine and non-specific immune treatments could be enough in combination to tip the balance in favor of the patient’s immune system so that it is able to overcome the cancer.

We’re going to further investigate how immune cells might help us to fight cancer and two head and neck cancer immunotherapy trials are due to start at the University of Southampton in the next six months.

One of these trials will look at a HPV cancer vaccine, while the other will investigate a non-specific immunotherapy molecule for those 70% of patients that develop head and neck cancer independent of HPV. Our hope is that within five years the results of these trials could influence the way we treat cancers.The Conversation

Note: This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.