Katie Couric’s talk show “Katie” has drawn ire from doctors and journalists for a recent segment on the HPV vaccine that presented what it called “both sides” of the “HPV controversy.”

The segment included personal stories from two moms who claim their daughters suffered serious harm from the vaccine (one of them died). In addition, the show featured two physicians: one who researched the vaccine and thinks its long-term protection benefits are oversold, and one who recommends it to her patients, in line with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

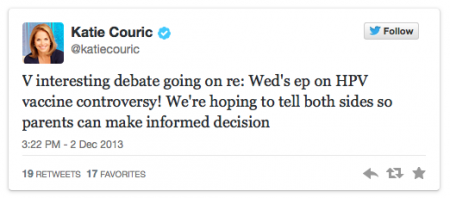

Ahead of the show, which aired Dec. 4, Couric tweeted:

Dr. Arthur Caplan, director of the division of medical ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City, did not feel it was appropriate to juxtapose the anecdotal stories with the medical evidence. He had hoped more weight would be given to the scientific evidence of the vaccine’s safety profile and effectiveness at preventing cervical cancer.

“The show was kind of inexcusable in terms of damage done versus positive contribution,” he told CBS News.

Any time you’re vaccinating hundreds of thousands of people, Caplan said, you can expect that some people in that population will have health incidents occur. But their ailments may not necessarily be connected to the vaccine. What needs to be weighed is the cause and effect, versus what may be just coincidence. Mentioning such incidents in that context would have been one thing, but giving them more air-time than the bevy of evidence about safety and efficacy is another.

“The problem in TV and all media, (is) the human interest drives the story,” said Caplan. “In science and public health, it doesn’t, or it’s at risk of grave harm.”

“If you want to do a show every day that spotlights anecdotal claims about the health effects of cell phones or curative powers of megavitamins or dangers of airplane contrail vapors, you can certainly fill up lots of programming,” said added. “But I don’t think you’re doing anyone a service.”

While the show has certainly sparked debate, what’s not debatable is that HPV is a significant factor in cancer cases in the United States.

Human papillomavirus, or HPV, is an infection that is so common that it will occur in virtually all sexually-active people at one point or another. About 79 million Americans are currently infected with HPV, according to federal estimates.

There are more than 150 related viruses that make up HPV, but about 40 can be transmitted sexually, and some play a bigger role in causing genital warts while others increase risk for cancers of the cervix, anus, oropharynx (throat and back of the tongue), vulva, vagina and penis.

About 90 percent of genital warts are caused by the HPV 6 and 11 strains, while the majority of cancers related to the infection — about 70 percent — are caused by strains 16 and 18.

But most people won’t have a problem. The CDC points out 90 percent of all HPV infections, including the cancer-causing strains, will be cleared or undetectable in two years without any treatment, with many leaving the body within six months due natural immunity.

It’s the ones that don’t clear that are worrisome. Virtually all cervical cancer cases each year – there are 12,340 new ones expected in 2013 — are caused by high-risk strains of HPV, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Rates of oropharyngeal cancer have soared in recent years, studies have found, and HPV from oral sex is thought to be to blame, as Michael Douglas spotlighted in June by disclosing his throat cancer was caused by the infection.

That’s where vaccines aim to help, by preventing HPV in the first place. The two approved vaccines are Cervarix, which prevents HPV types 16 and 18, and Gardasil, which prevents HPV 16 and 18 as well as the genital-wart causing HPV 6 and 11 strains.

Both vaccines are given in three doses over a six-month period, recommended for females aged 13 through 26, and males between 13 and 21 years old.

“The vaccines that are available right now are one of our only protections against HPV,” Dr. Nieca Goldberg, director of the Joan H. Tisch Center for Women’s Health at NYU Langone Medical Center, told CBS News in June.

A CDC study in June reported rates of HPV strains related to genital warts and some cancers have dropped 56 percent among American teen girls since a vaccine was introduced in 2006, from 11.5 percent of 19-year-olds infected before the vaccine was introduced, to 5 percent by 2010.

Dr. Diane Harper, chair of family medicine at the University of Louisville who researched the vaccine, told Couric that the vaccine’s protection wears off after five years, so men and women could still be at risk for HPV down the road.

The CDC, however, says studies with up to six years of follow-up data have found no evidence of waning effectiveness from the vaccine, a point Caplan also emphasized. One study found even one dose was 82 percent effective, though all three doses are recommended.

The CDC adds that if 80 percent of teens got all three doses of the vaccine, an estimated 53,000 additional cases of cervical cancer could be prevented over the lifetimes of girls aged 12 and older. For every year that increases in coverage are delayed, another 4,400 women will go on to develop the disease.

That’s not to that say the HPV vaccine, or any vaccine, can’t cause side effects.

The CDC’s Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) has received at least 22,000 reports of adverse events in girls and women who got the vaccine between June 2006 through March 2013. Over this time, about 57 million doses of the vaccine were distributed in the United States.

Ninety-two percent of the reported side effects were considered nonserious. They included injection-site pain and swelling, fainting, dizziness, nausea, headache, fever and hives.

The other almost 8 percent of serious side effects included headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, dizziness, fainting and generalized weakness.

“Editors, producers want a face,” said Caplan. “Public health wants data, statistics, and boring compilations.”

* This news story was resourced by the Oral Cancer Foundation, and vetted for appropriateness and accuracy.

http://worldofdtcmarketing.com/irresponsible-journalism-that-can-cause-loss-of-life/in-the-news/

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.