- 7/25/2006

- Australia

- Alice Bergin

- EurekaStreet (www.eurekastreet.com.au)

The Federal Government has fired up its anti-smoking campaign with new national regulations forcing tobacco companies to include large colour photos of diseased and cancerous body parts on cigarette packs.

Previous anti-smoking warnings have proven to be impotent against the ‘evil’ and vicious cycle of nicotine addiction and it seems smokers’ attempts to kick the habit would continue to be futile without these other more strident warnings and bans planned to come into force state by state.

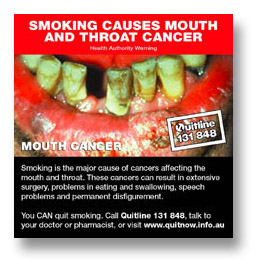

So instead of the tamer text warnings that have become so ubiquitous, smokers are seeing a range of photographs of lung disease cases, tongue cancers and even a dissected brain. As of 1 March 2006, it has been obligatory for these warnings to cover 30 per cent of the front and 90 per cent of the back of the box. The graphics are meant to leave no doubt about what medical experts already know – that smoking kills.

These new regulations are part of a series of recent changes that include the implementation of a nationwide policy of smoke-free pubs as well as other enclosed public spaces.

Tobacco smoking is a serious public health problem. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 17 per cent of Australians aged older than 14 years smoke daily. That’s about 3.4 million people. These people make up our beloved families, friends, neighbours and work colleagues. They commit themselves to a life plagued by lung and heart disease and potentially to cancer of the mouth, colon and every organ in between. Their passive smoke has also been implicated in reduced birth weights, lower respiratory illnesses and chronic respiratory symptoms in children.

Globally, tobacco products are responsible for one in ten adult deaths each year (about five million people). But why do so many still insist on inhaling?

Tobacco is profoundly addictive and the culprit is nicotine. Nicotine addiction is one of the most prevalent addictive behaviours worldwide. The physiological basis for nicotine addiction has been hotly debated for more than 40 years. A current theory proposes that nicotine has a dual response in the body. Initially, it stimulates the pleasure response from the brain but when taken over longer periods, it creates a relaxed state.

Like a double-edged sword, nicotine withdrawal is a painful one, disproportionate to the pleasure often attributed to it. Withdrawal symptoms are time-limited and proportional to the depth of nicotine dependence. They include anxiety, irritability, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, tobacco craving (no huge surprise there), gastrointestinal problems, headaches and drowsiness.

So having a drag makes you feel good and stops making you feel bad. Simple really — need I go on?

Quitting is very difficult, there’s no doubt. The breadth of smoking cessation programs supports this. Behavioural interventions (physician advice, counselling and social supports), nicotine replacement (gum, patch, inhaler and nasal spray) and anti-depressants are the mainstay of most programs. Acupuncture, hypnosis, aversive therapies and exercise programs are touted as alternatives. Despite this, the long-term abstinence rates are somewhat pitiful – less than 25 per cent.

It’s not hard to understand why. Aside from the physical pain of withdrawal, smoking is a powerful social tool. Asking someone for a light may start a conversation that finishes with a coffee date. The ‘smoko’ is a tradition of sorts, part of Australian culture. Picture a gathering of like-minded individuals, forced to engage in the activity against a backdrop of the biting-cold Melbourne wind, whilst smug ‘others’ sip lattes, shrouded in an angelic glow, warmed by the haze of their ducted heating system.

Tobacco companies are required to adequately inform consumers about the risks, but have they? The right of accurate information is a fundamental consumer value. No smoker can be reasonably expected to fully appreciate all the risks associated with their ostracised behaviour. The tobacco industry claims that smokers are fully-informed about the risks, but this information appears superficial and without true understanding.

As part of the new national changes, a general warning on the toxicity of cigarettes will replace details on nicotine, carbon monoxide and tar content, and packets will carry a phone number and web address for the national Quitline.

These changes are vital in making a lasting impression on potential smokers. Do you think a 16-year-old girl who lights up in an attempt to impress school friends really understands the cigarette could lead to a nicotine addiction? Or do you think she realises this addiction could cause chronic airways disease, to such an extent that she needs to carry an oxygen tank with her at all times? Or that the airways disease could be so disabling, she may get short of puff trying to go to the toilet, thus forcing her to a life of incontinence pants and bed pans? Would she realise that it could cause her to have a stroke, thus rendering half of her body immobile? Despite all of these distractions, she still must attend her day centre three times a week for dialysis for her kidney failure, and chemotherapy for lung cancer. It doesn’t sound like the sort of life any 16-year-old would wish upon themselves.

Is demonising smokers and smoking the answer? Amputated limbs, gangrenous toes, black teeth, holey and tarred lungs, young and old people on death’s door in hospital and milky porridge being milked from a ‘smoker’s aorta’ have become hallmarks of anti-smoking advertising in Australia.

Legislation passed in NSW and Victoria seeks to ban all indoors smoking in pubs and clubs from 1 July 2007. Many venues are constructing smokers’ havens in the form of largely covered and walled courtyards and beer gardens, allegedly to cushion the blow of the new regulations. Smoking is currently restricted to a single room or less than 25 per cent of the total indoor area. Queensland and Tasmania have already banned indoor smoking, while South Australia and the ACT are set to follow suit.

The anti-smoking lobby has painted an extremely unattractive portrait not just of smoking, but of smokers – the three-and-a-half million people, addicted to nicotine, who are also our friends and family.

As a result of this, could it be that smoking has become as much a sinful pleasure as an act of rebellion, rather than of self harm?

Shouldn’t we bring our smokers in from the cold? Could this acceptance help some to be anti-establishment in a less harmful way? Perhaps opening the door to these outcasts may help them on their road back to health.

So now we know why people smoke and why it’s so difficult to quit, but how do we use this information to stop people killing themselves? We can inform people about all the risks, the implications smoking will have on their lives and finally help them find methods to quit that suit them.

I have to admit something – I was one of them. Yes, me! I should have known better but, coffee in one hand, ciggie in the other – what a treat it was. But, I quit. Was it the warnings on cigarette packs? Fear of vascular disease? No, I just couldn’t breathe when I went for a run.

So whether you have the smoking habit already, or are bothered by passive smoking, you should already be noticing some drastic changes around the country. Non-smokers will be happy about further smoke-free spaces, and smokers will be facing the graphic and in-your-face evidence that they should become like their non-smoking role-models.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.